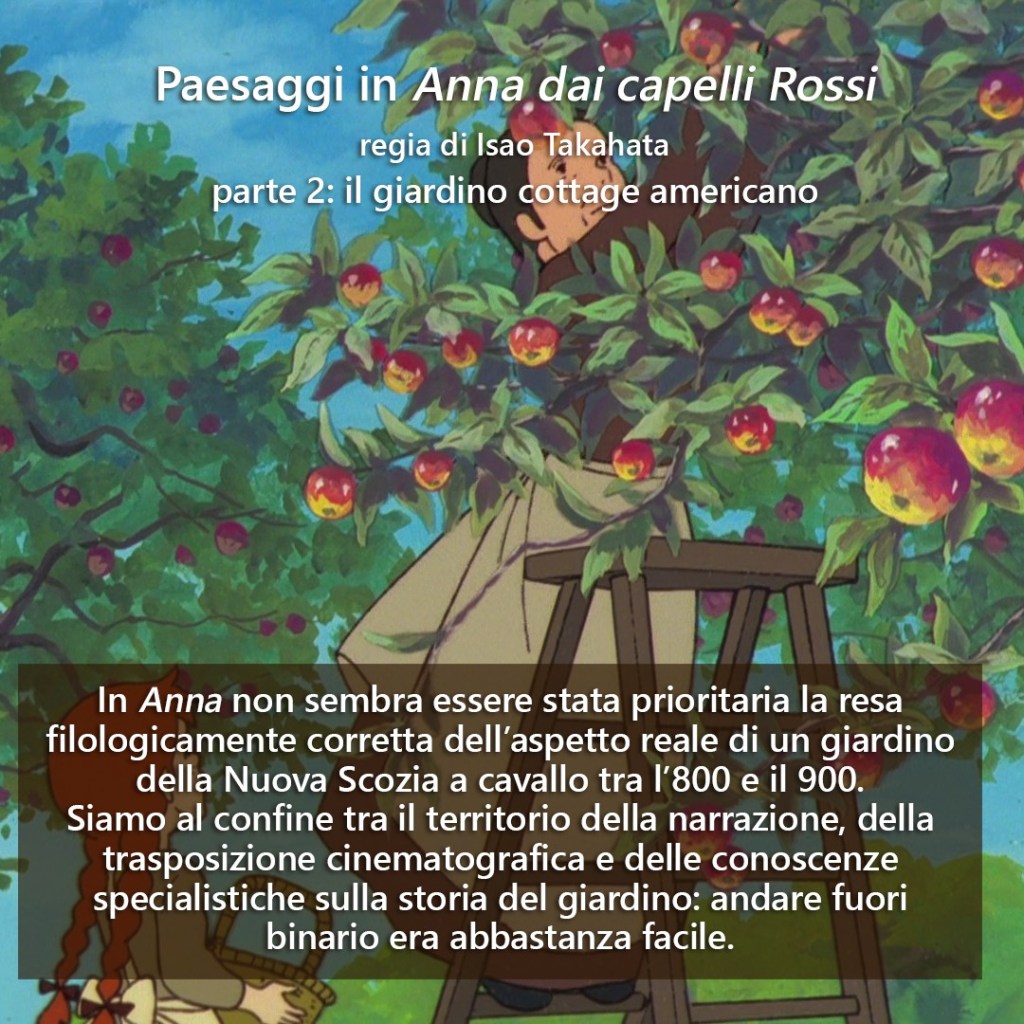

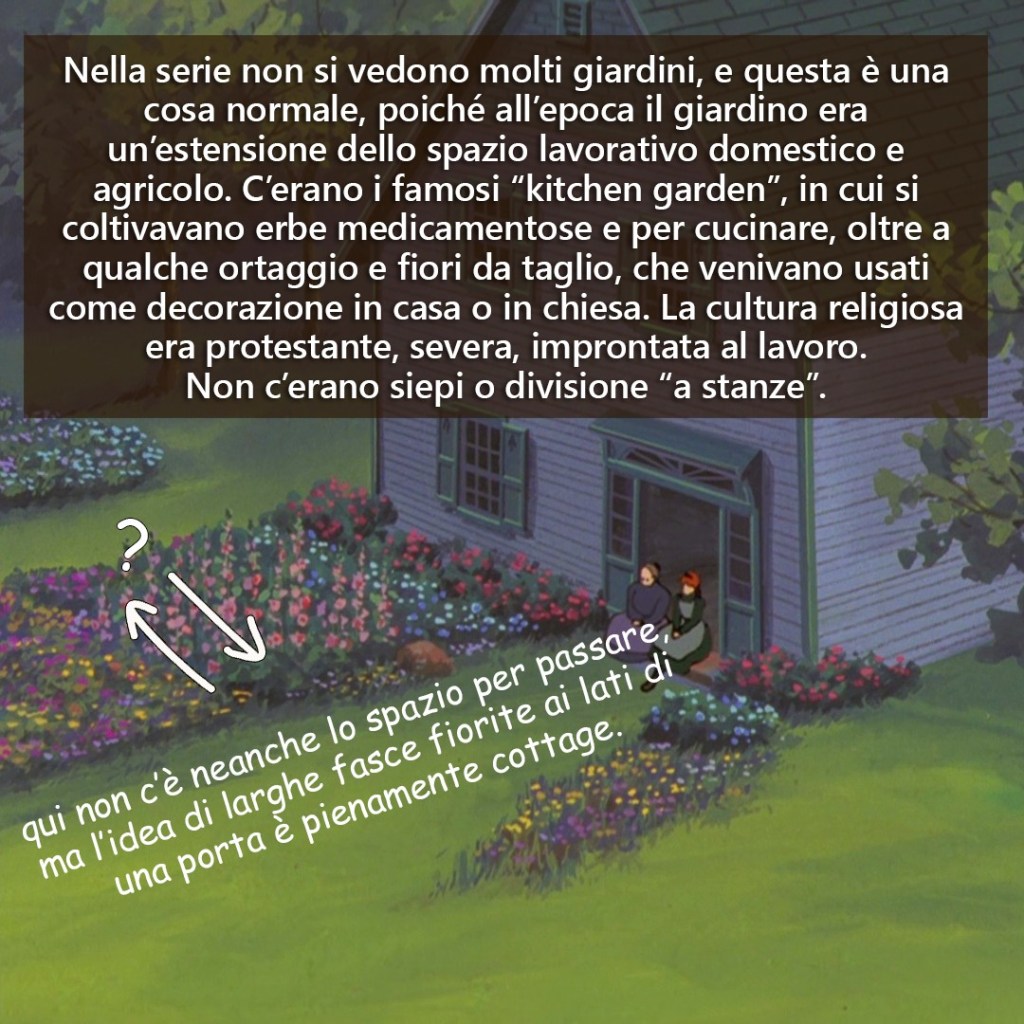

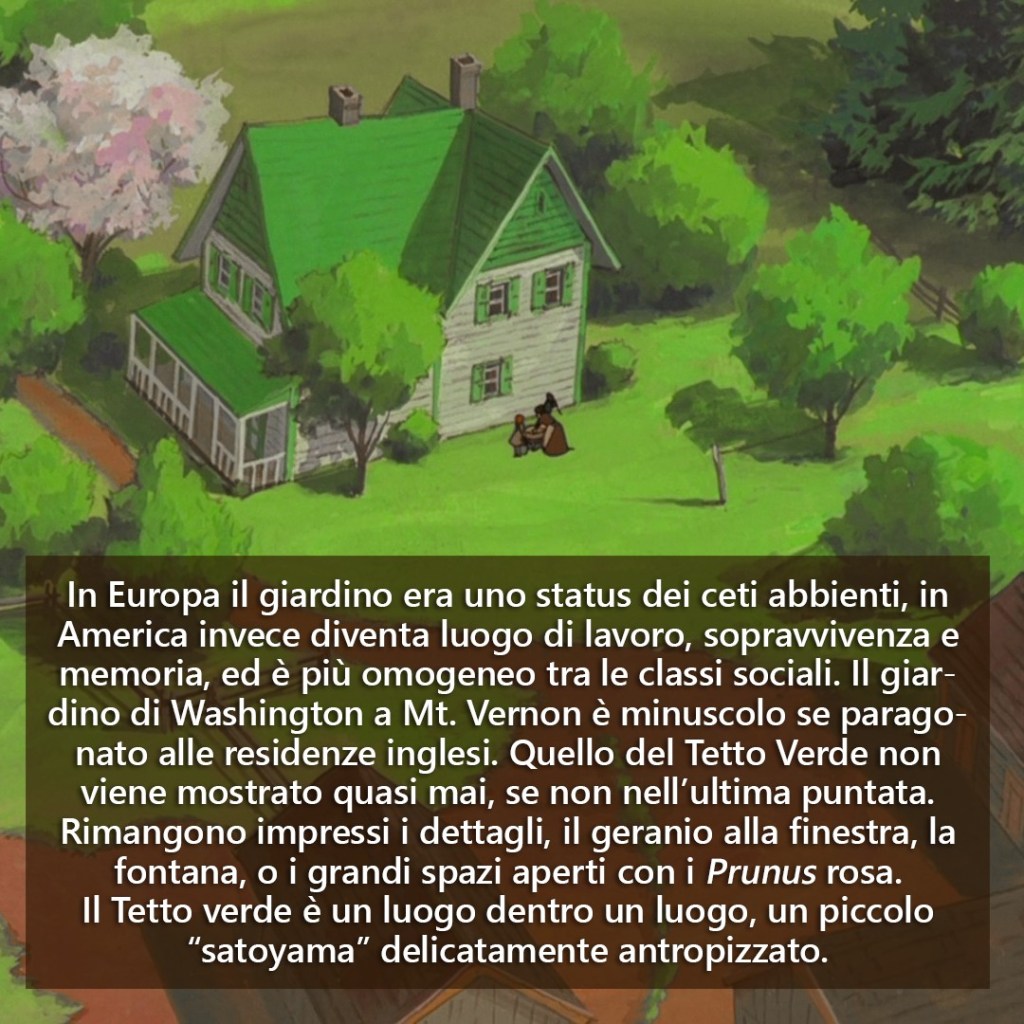

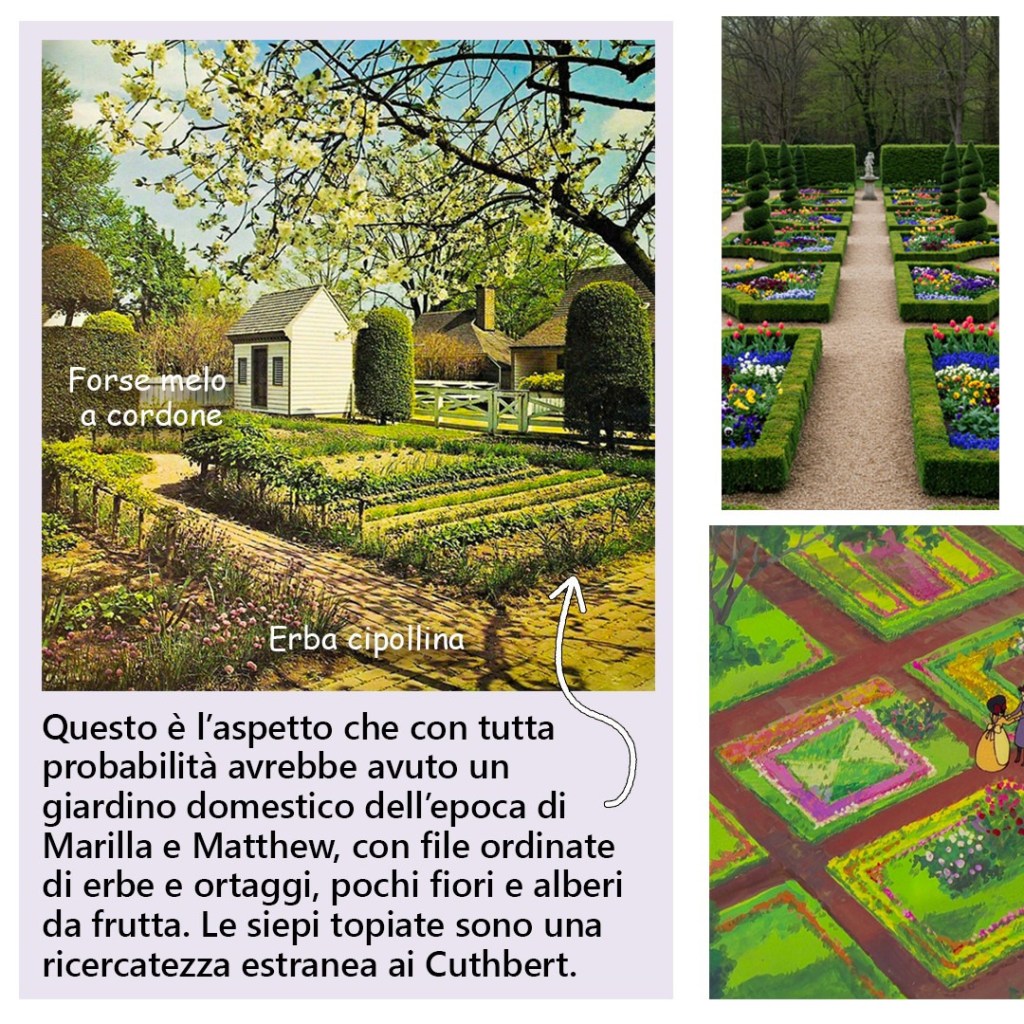

Ripropongo sul blog la serie di immagini che ho usato per due post su instagram (@lidiazitara)

Ripropongo sul blog la serie di immagini che ho usato per due post su instagram (@lidiazitara)

Ripropongo sul blog la serie di immagini che ho usato per due post su instagram (@lidiazitara)

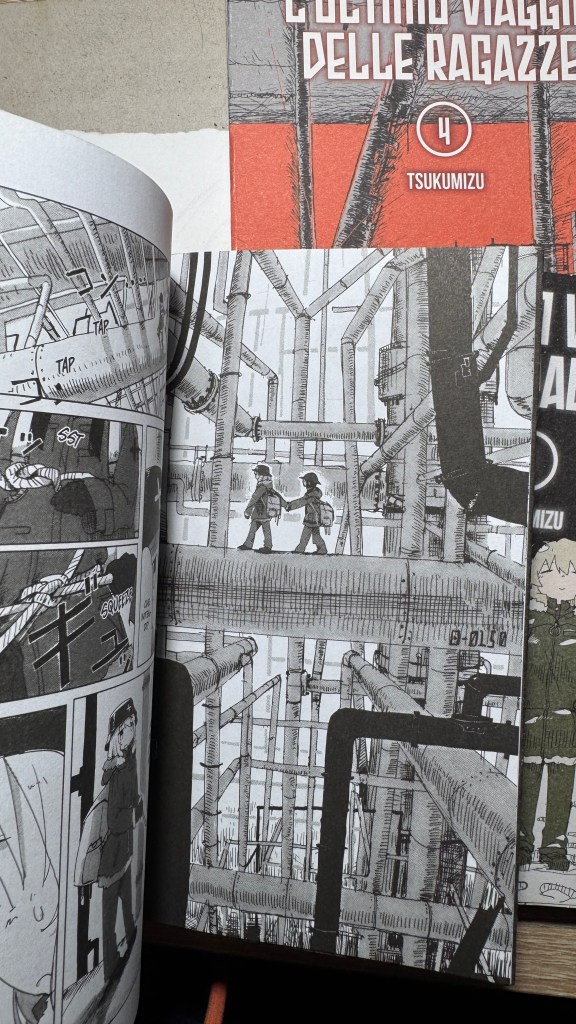

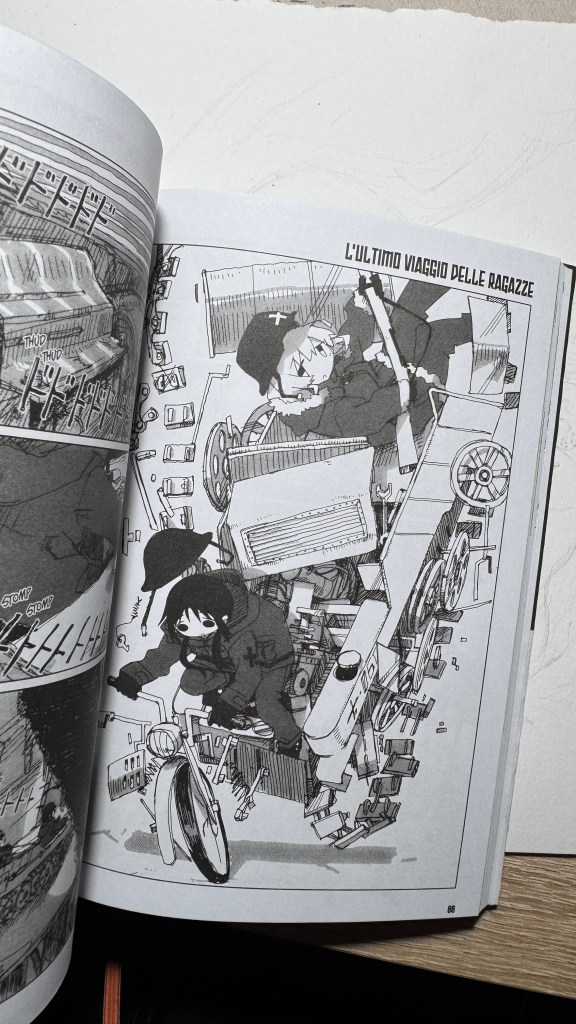

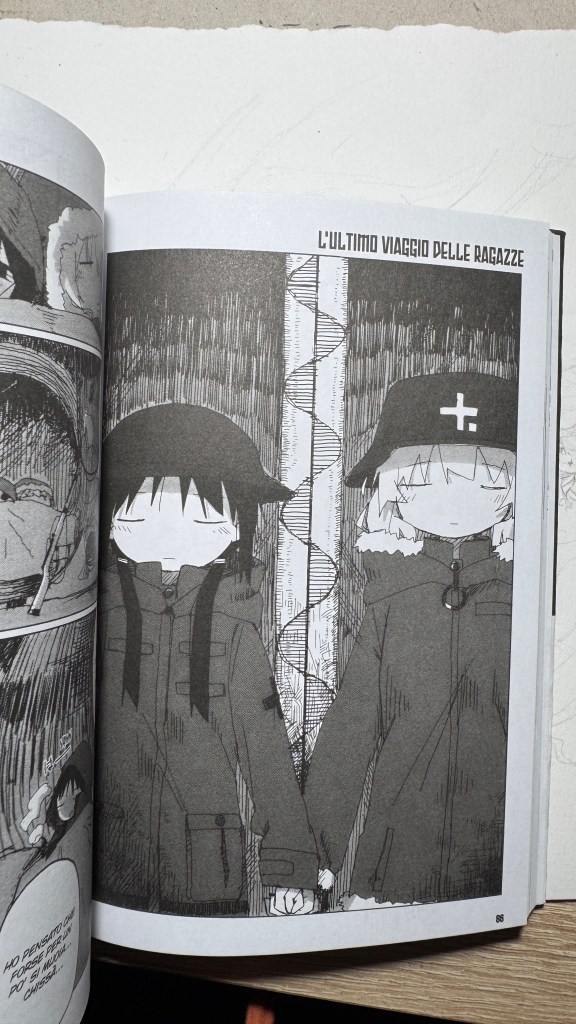

Sono anni che predico che i titoli originali di manga e libri vadano scritti con i kanji e non solo in rōmaji. L’ultimo viaggio delle ragazze gioca infatti sull’ambiguità della pronuncia “shūmatsu”, che all’orecchio può significare “fine settimana” oppure “fine del mondo”. Il titolo in kanji è 少女 終末 旅行, cioè “il viaggio delle ragazze fino all’apocalisse” (shūmatsuron è l’escatologia), ma potrebbe essere anche “la gita fuori porta nel weekend”.

Ed è su questo doppio senso che si basa Tsukumitsu, un vero volpone: i giapponesi sono entrati nel manga con una doppia attesa, o almeno un’aspettativa ambigua: sarà un racconto distopico, oppure uno slice of life? Noi no, ma oggettivamente era impossibile riprodurre l’omofonia in italiano (non dirò altro, perché questo piccolo capolavoro non va spoilerato in nessuna parte).

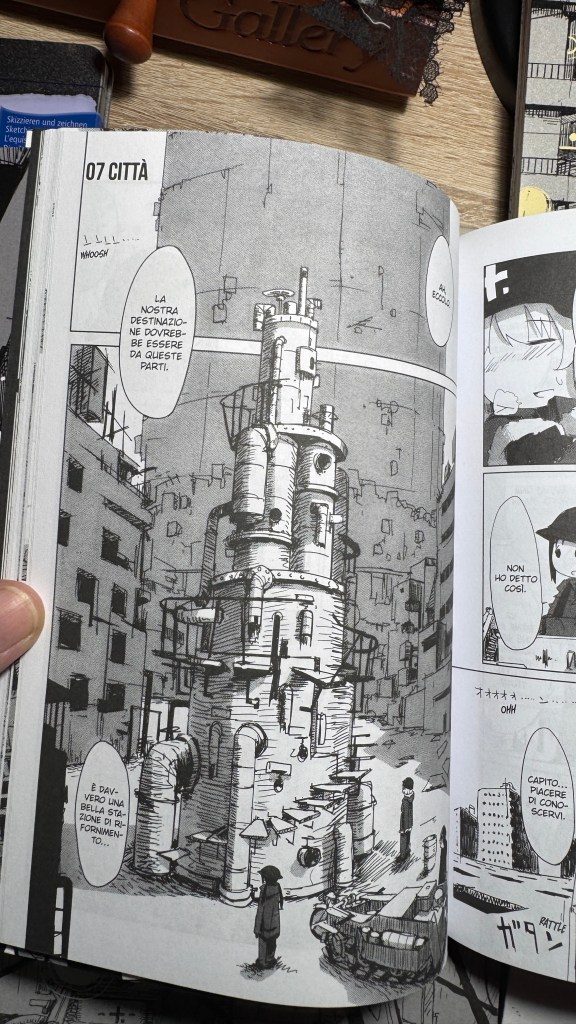

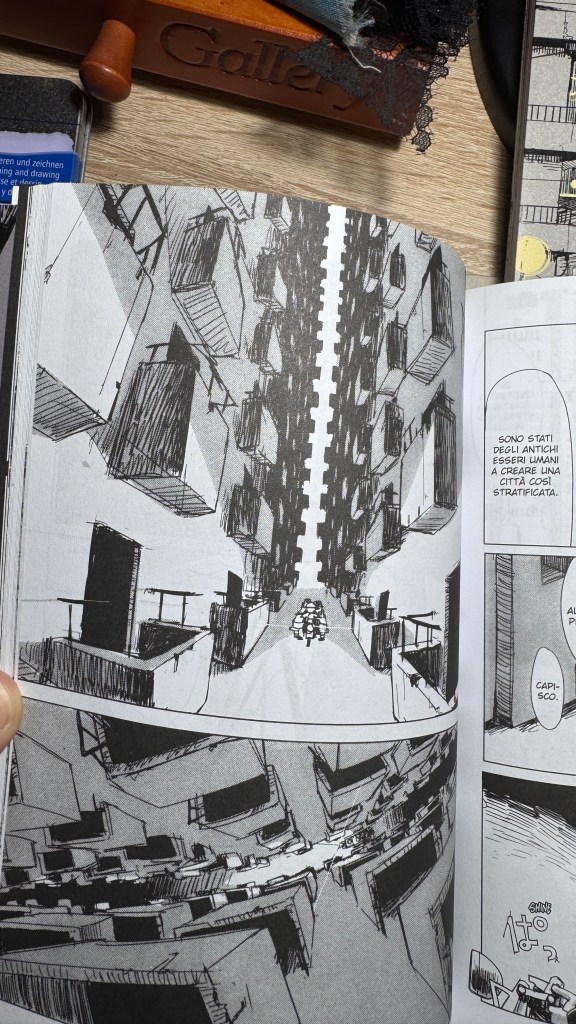

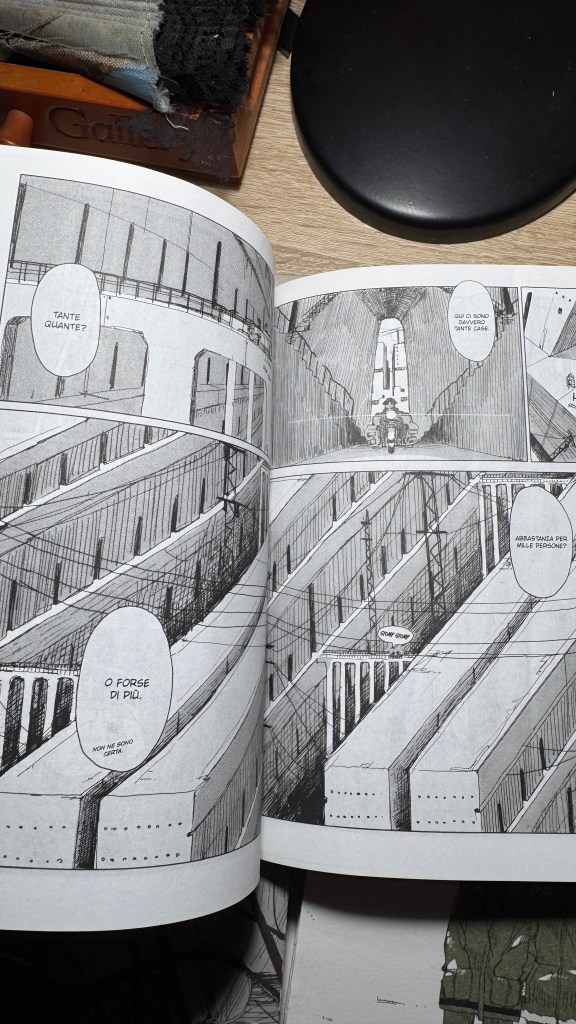

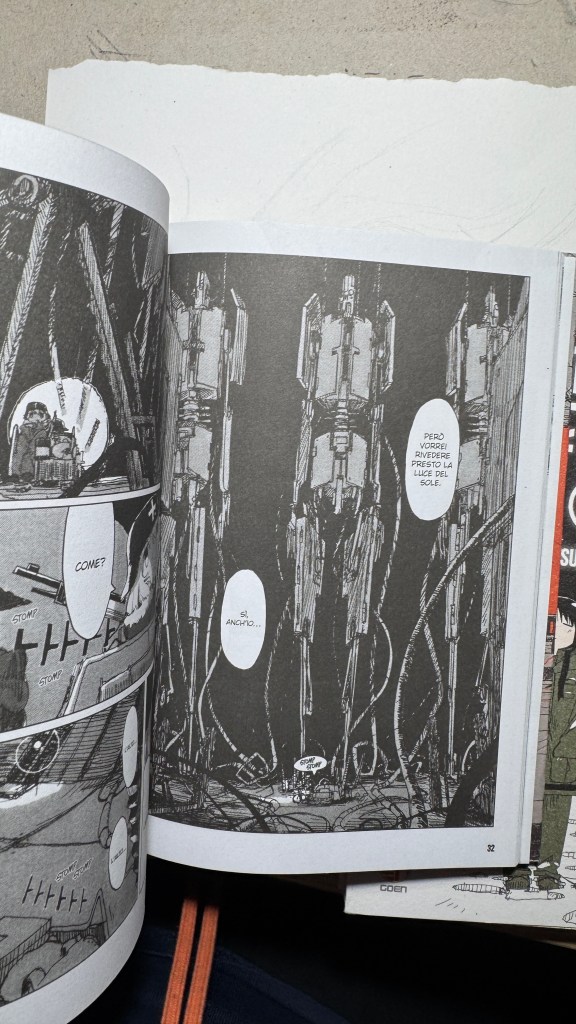

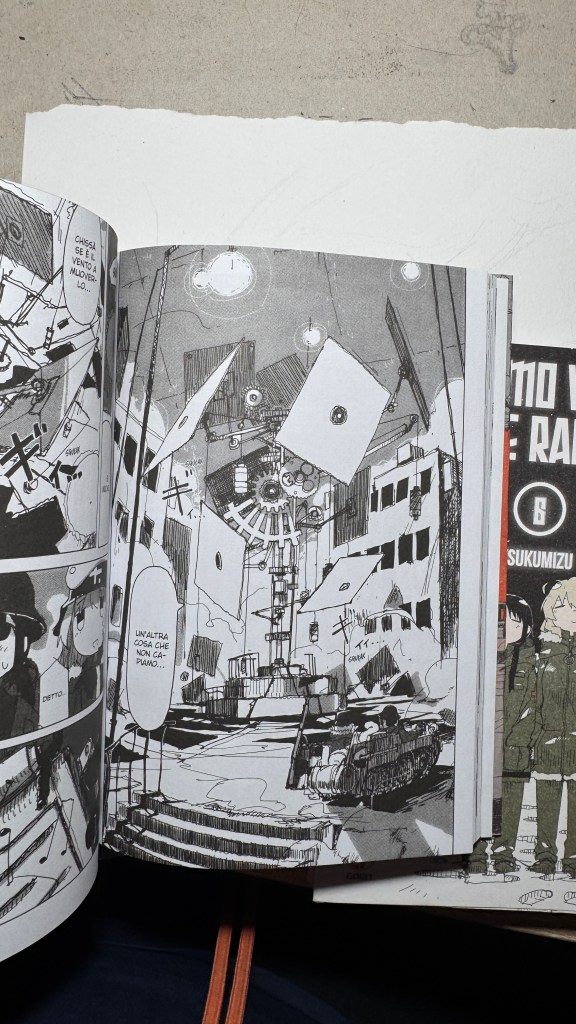

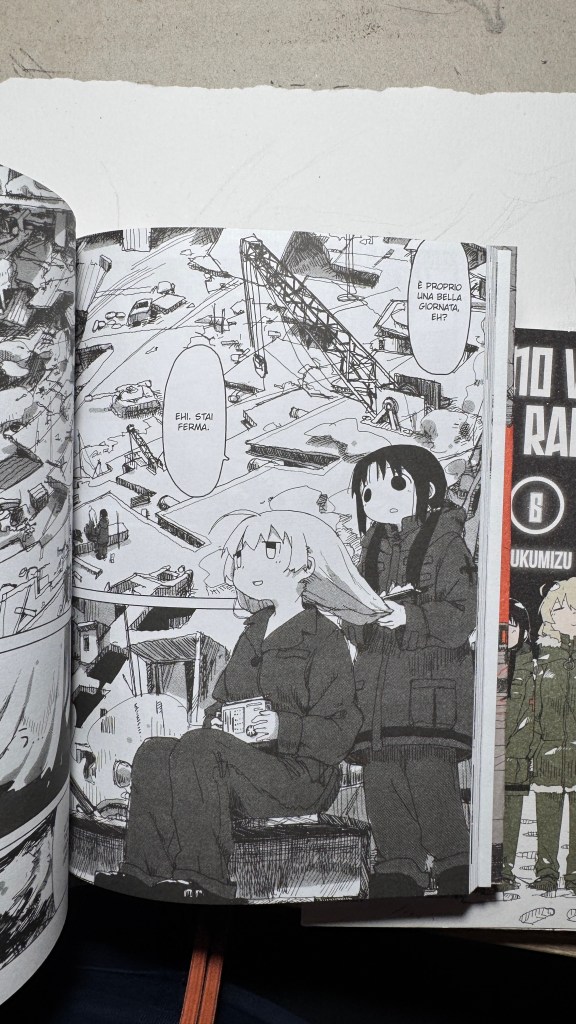

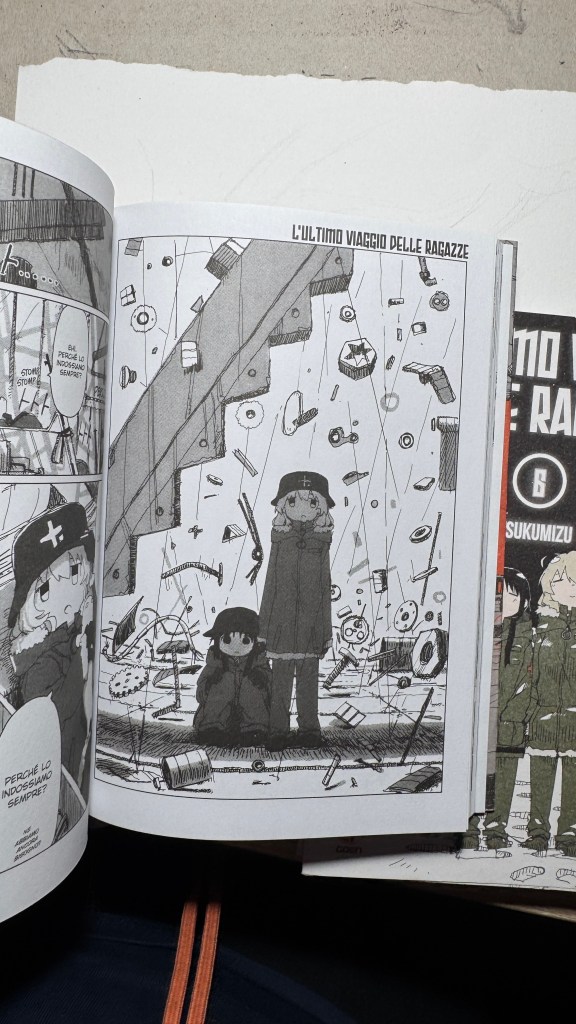

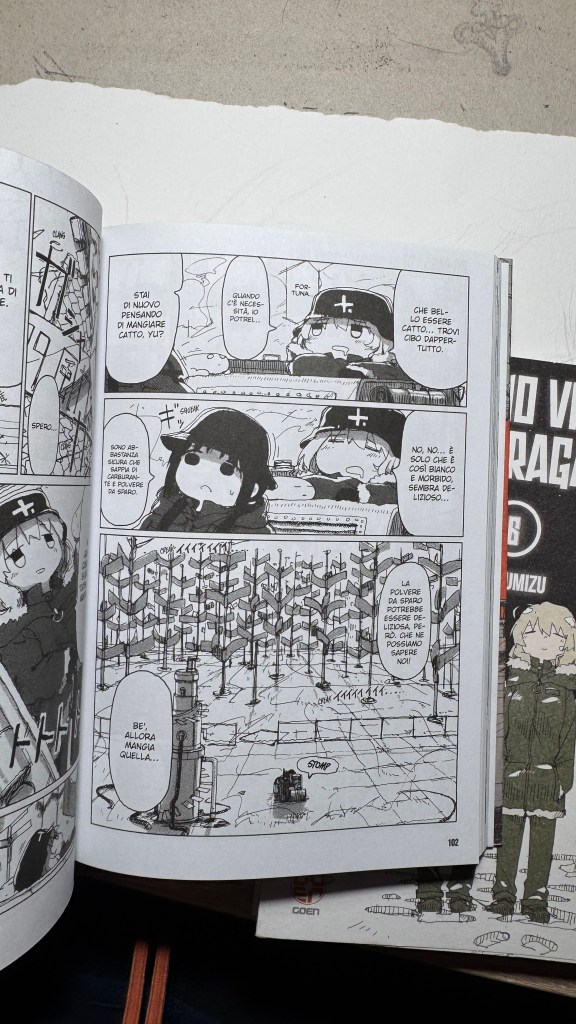

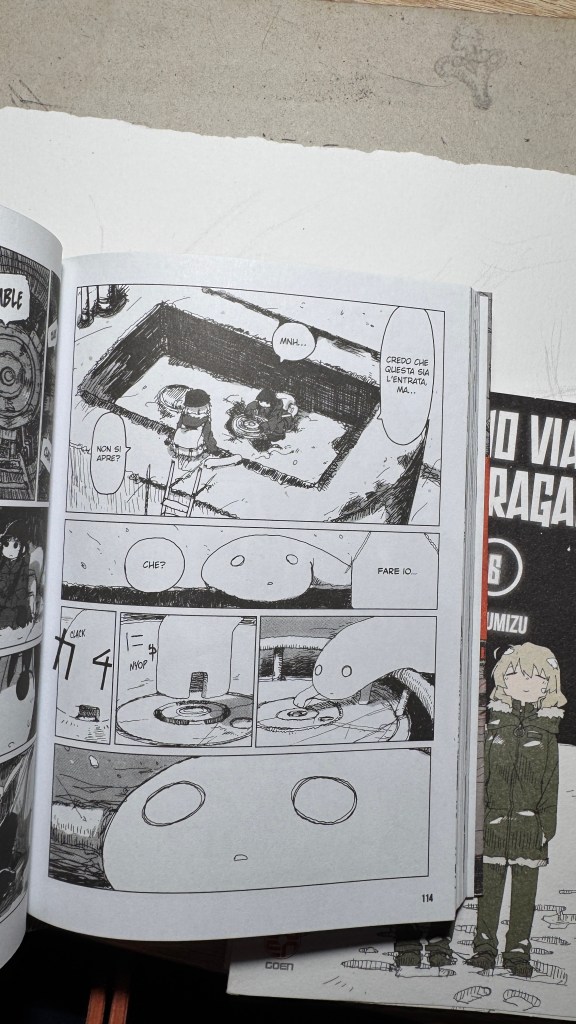

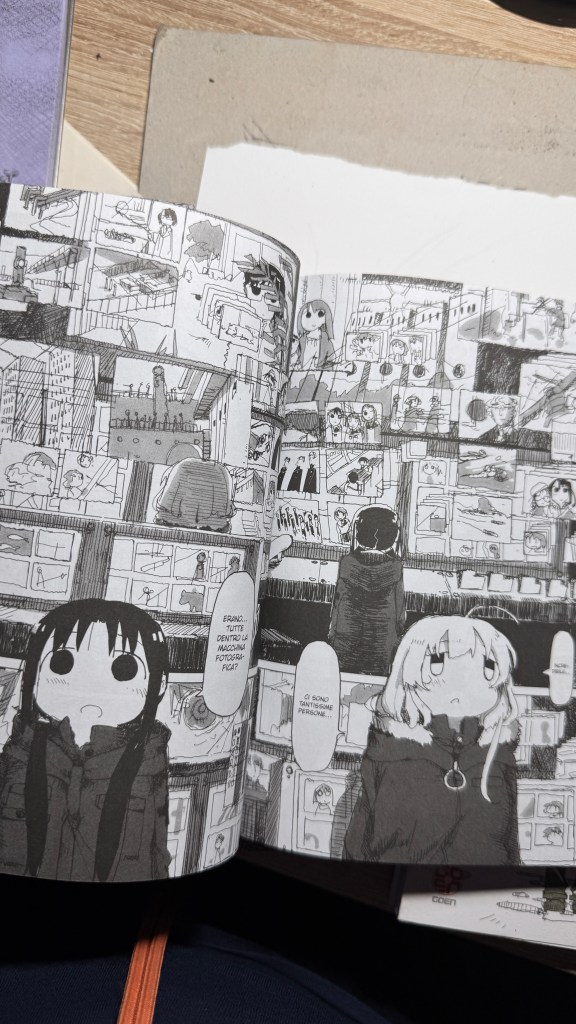

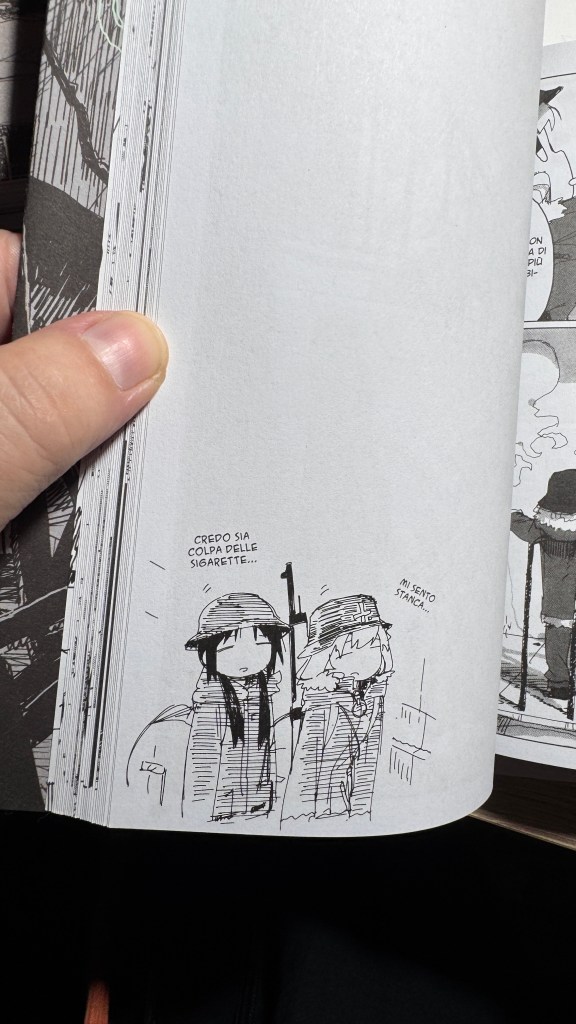

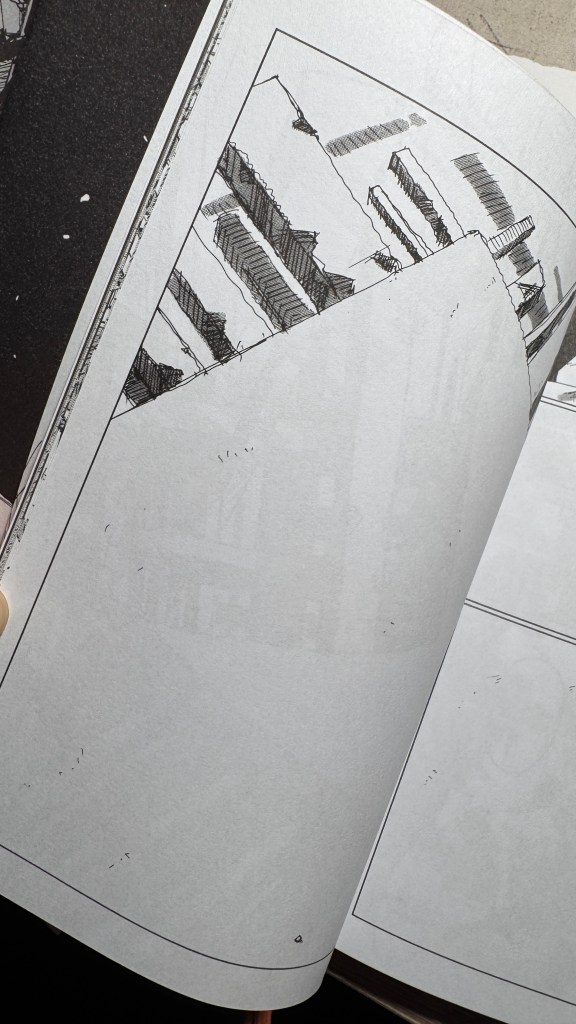

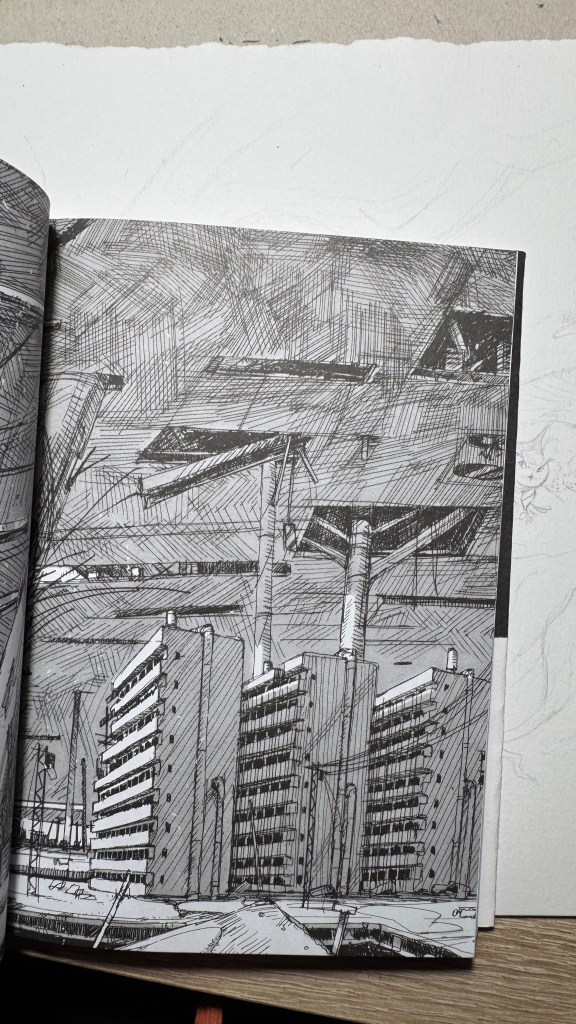

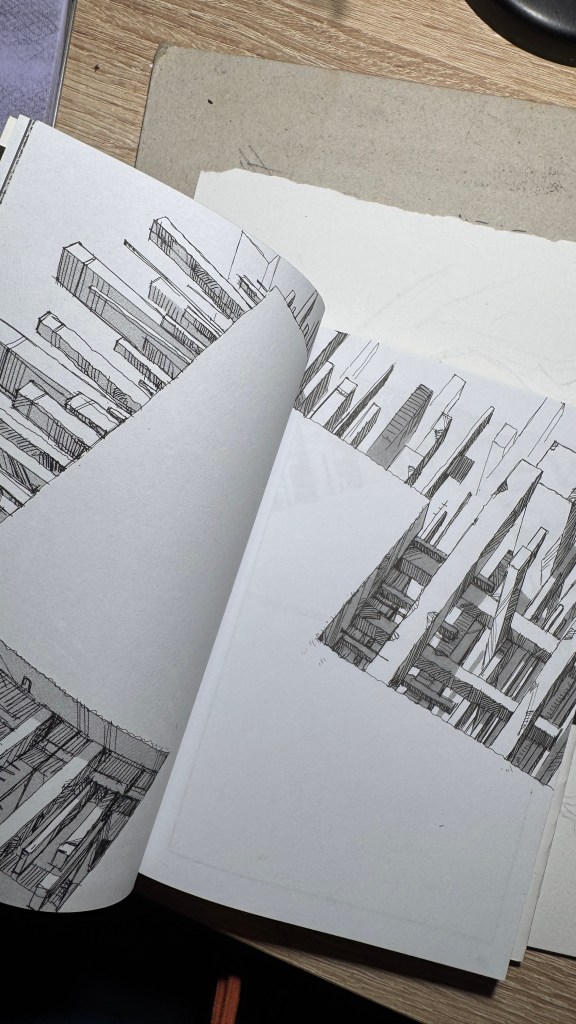

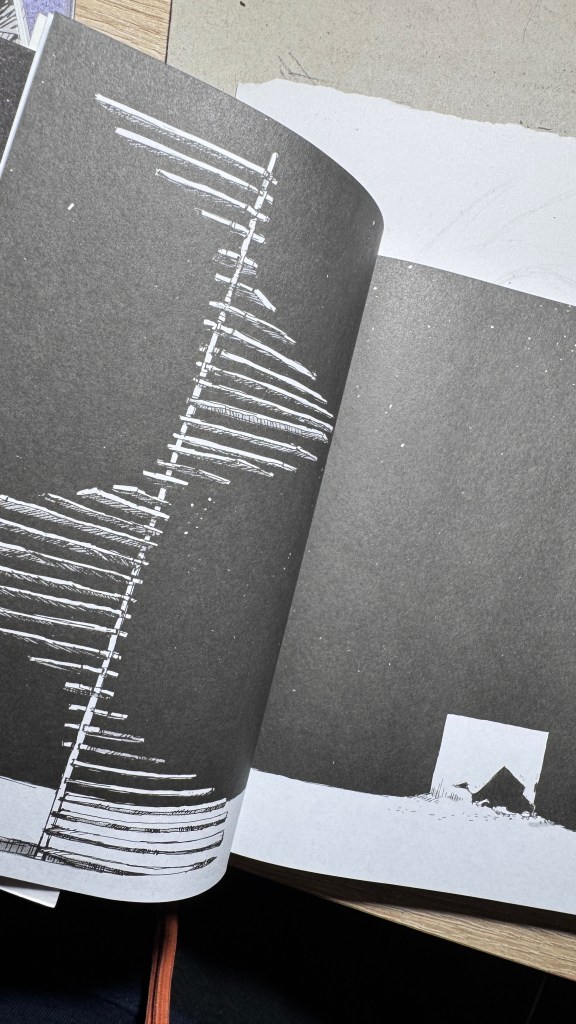

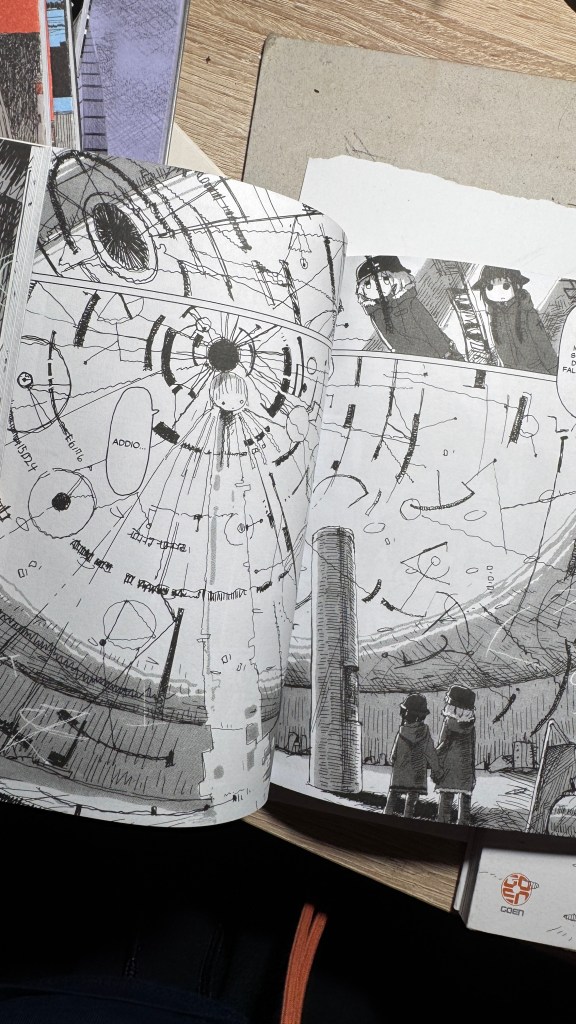

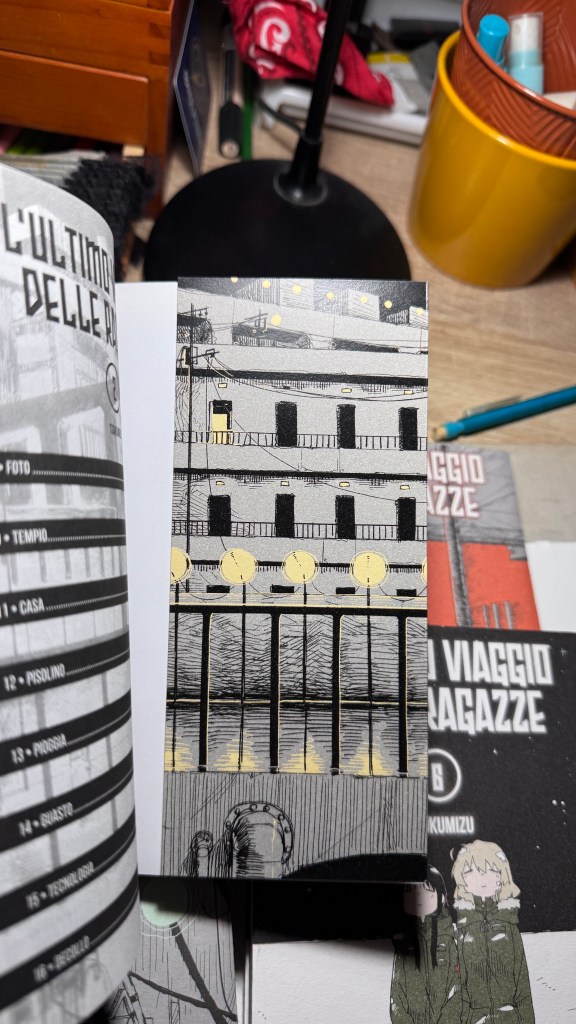

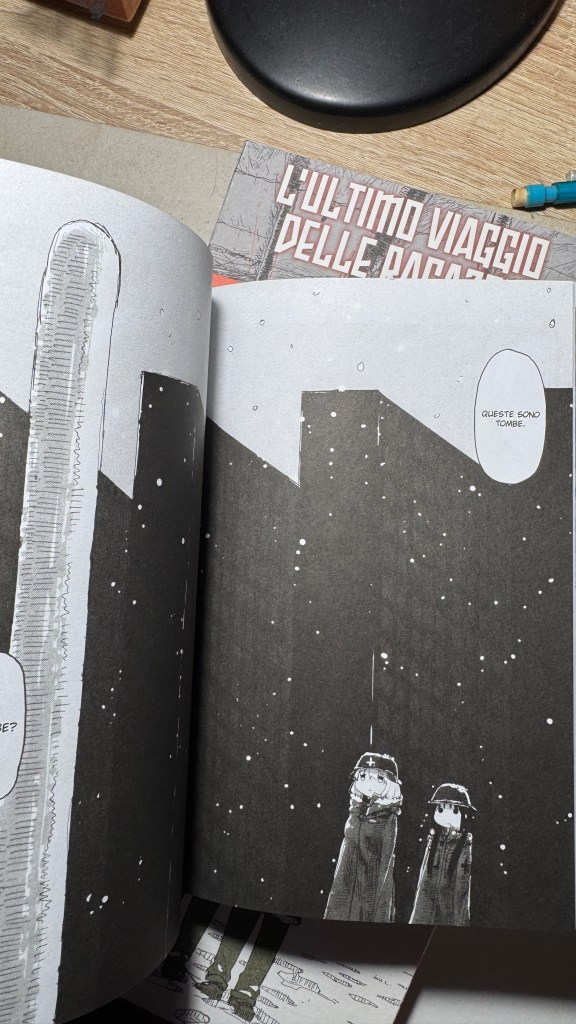

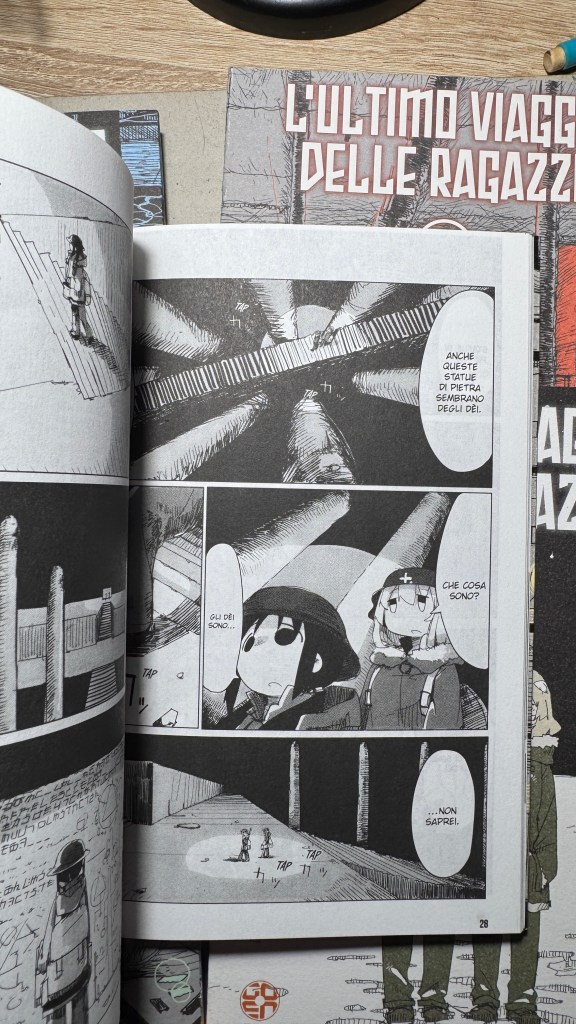

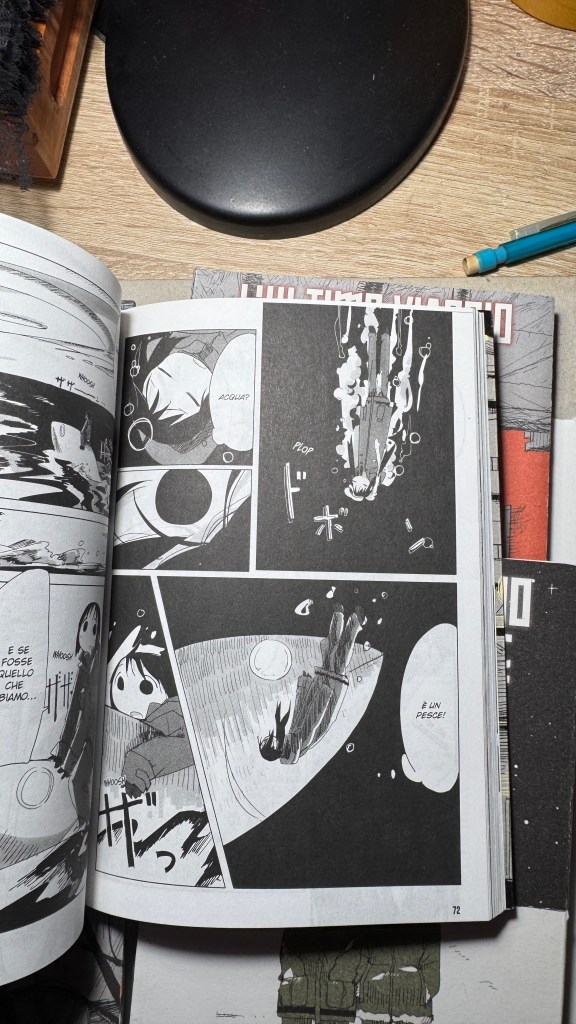

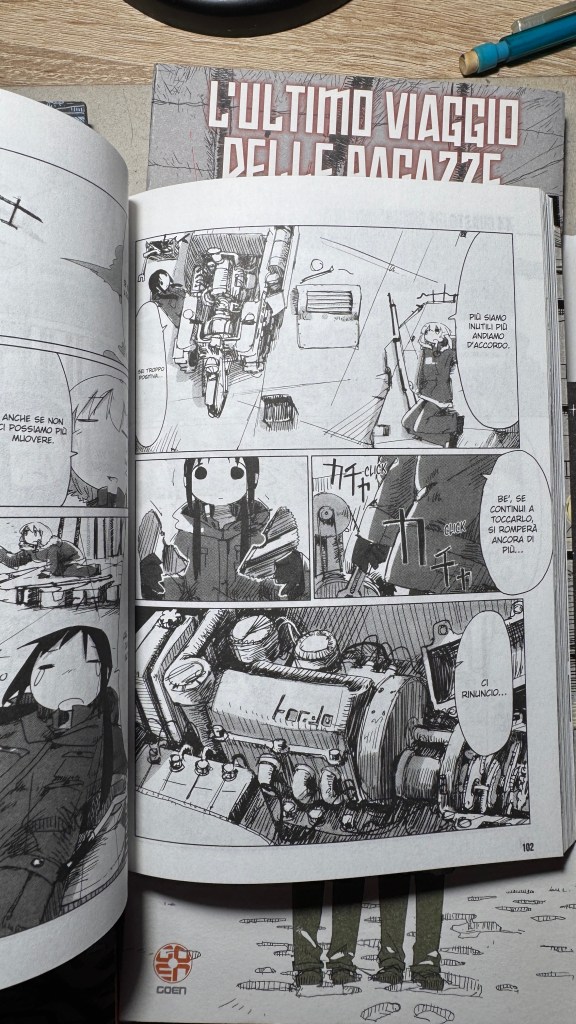

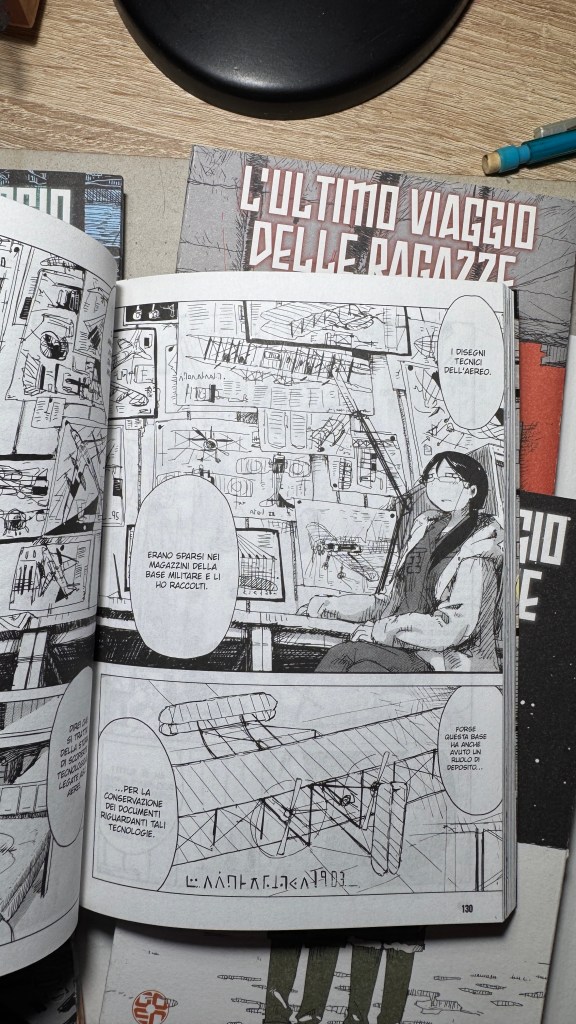

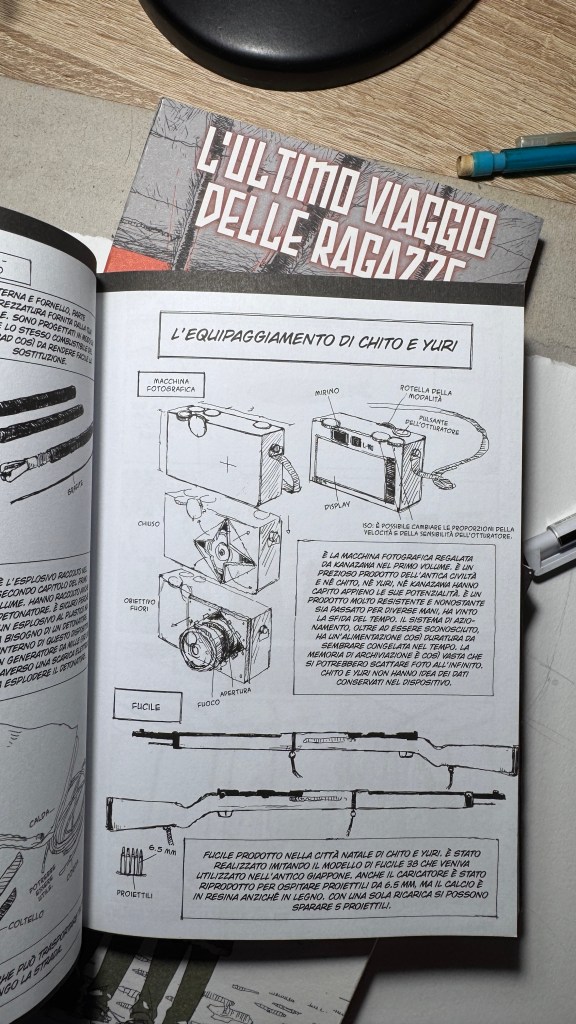

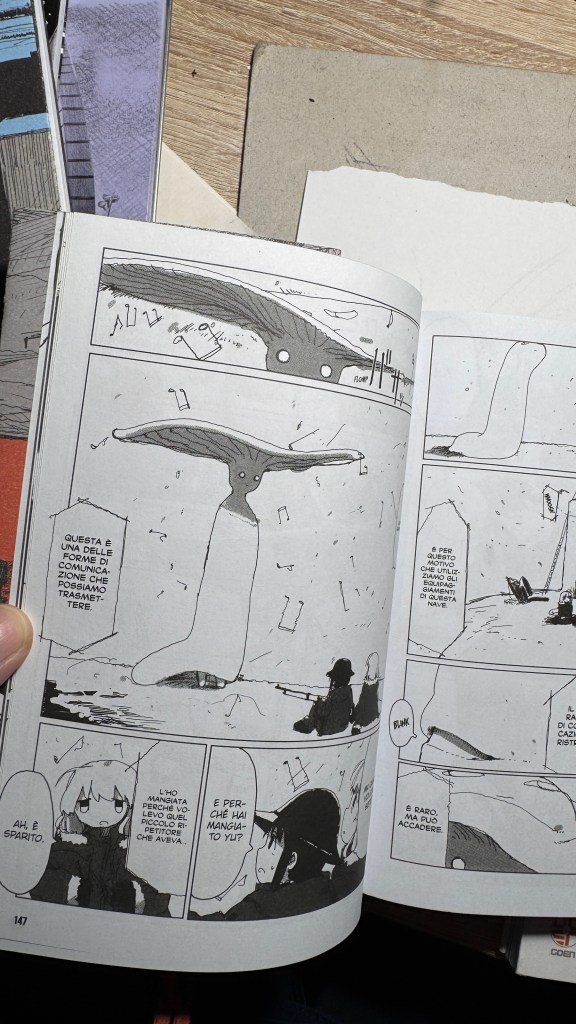

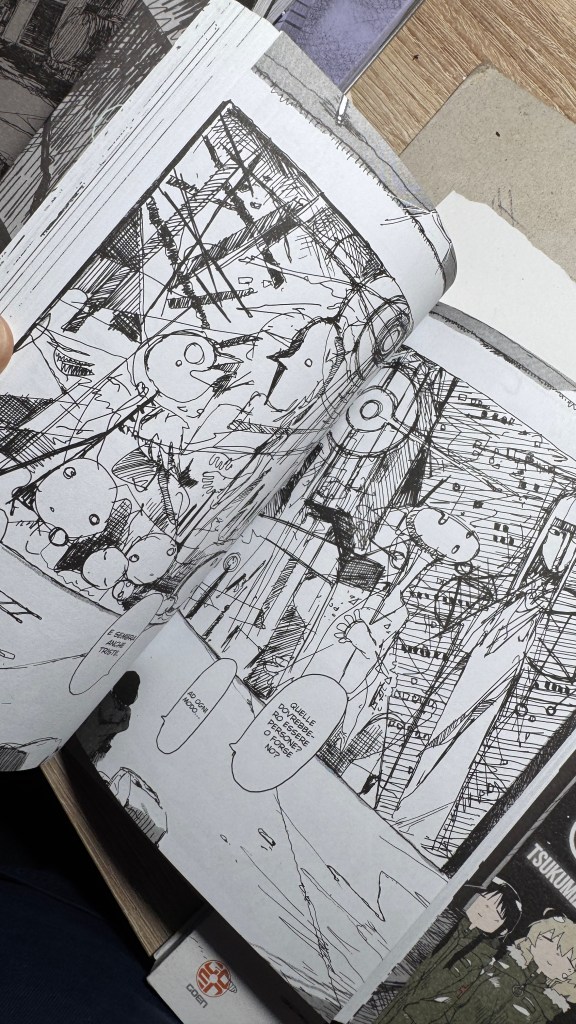

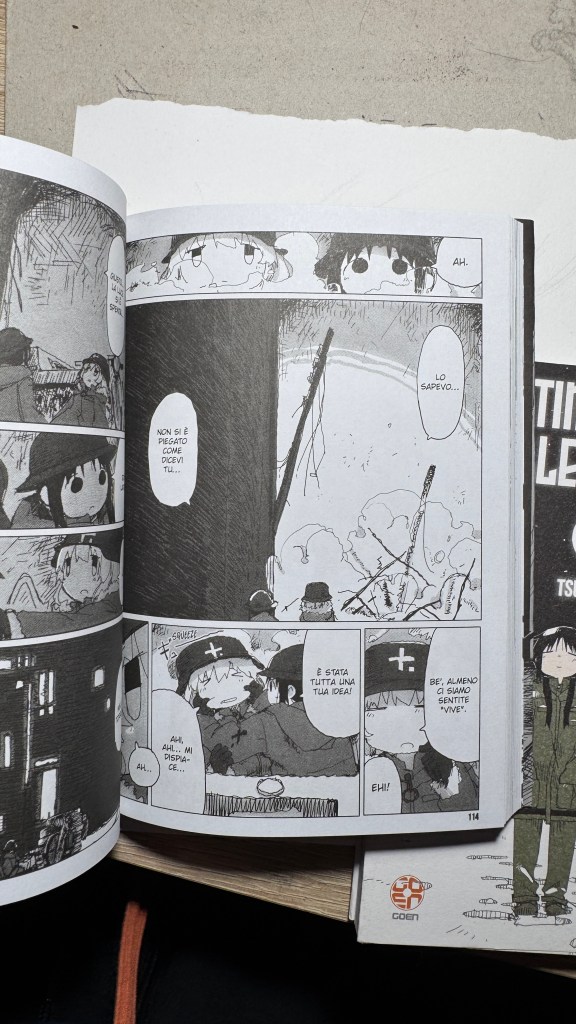

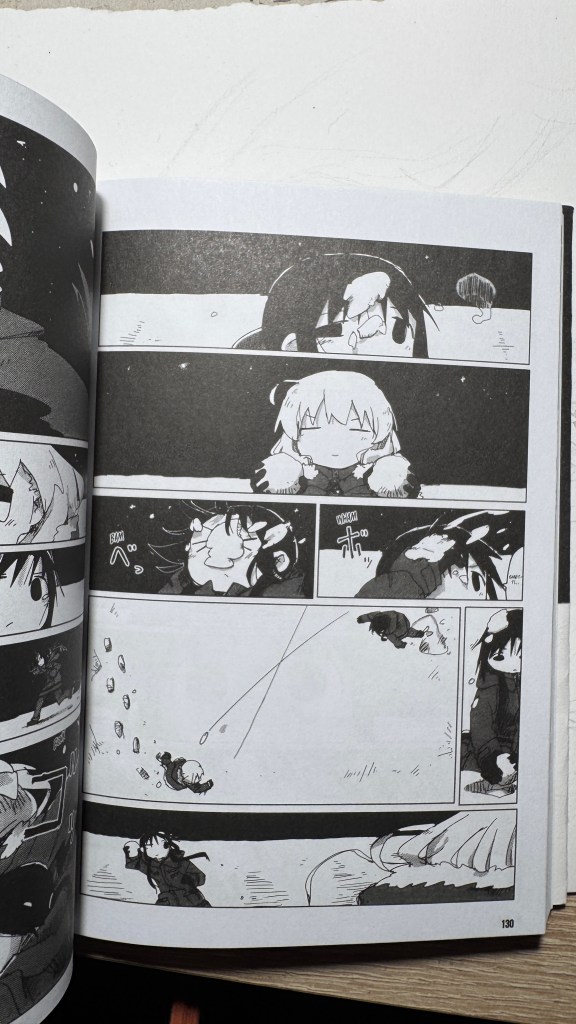

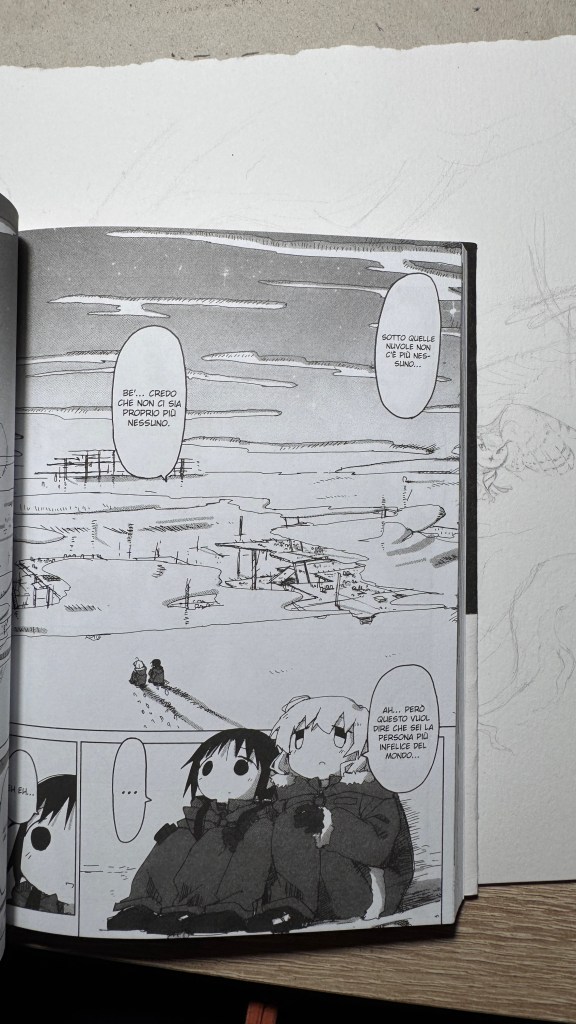

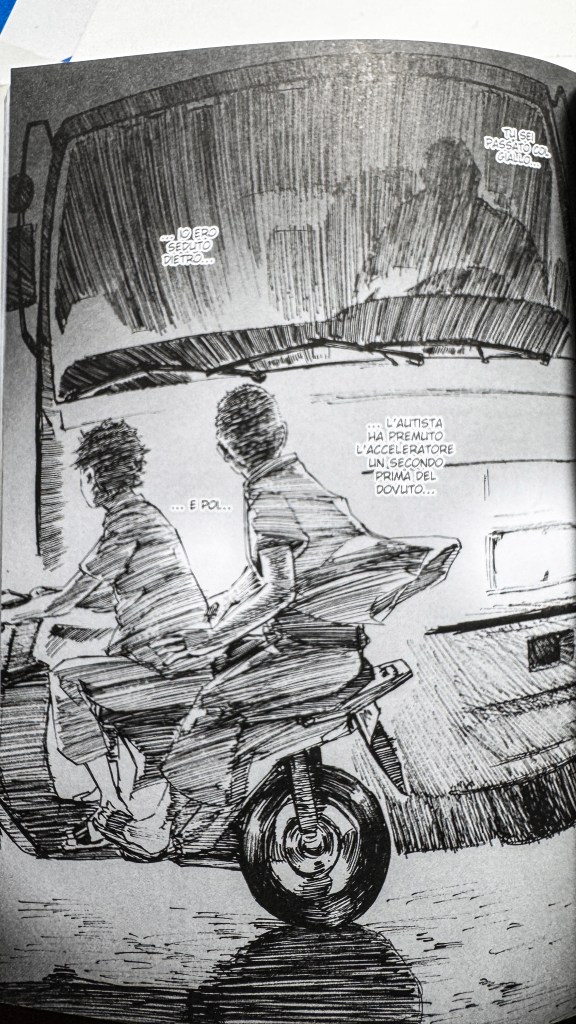

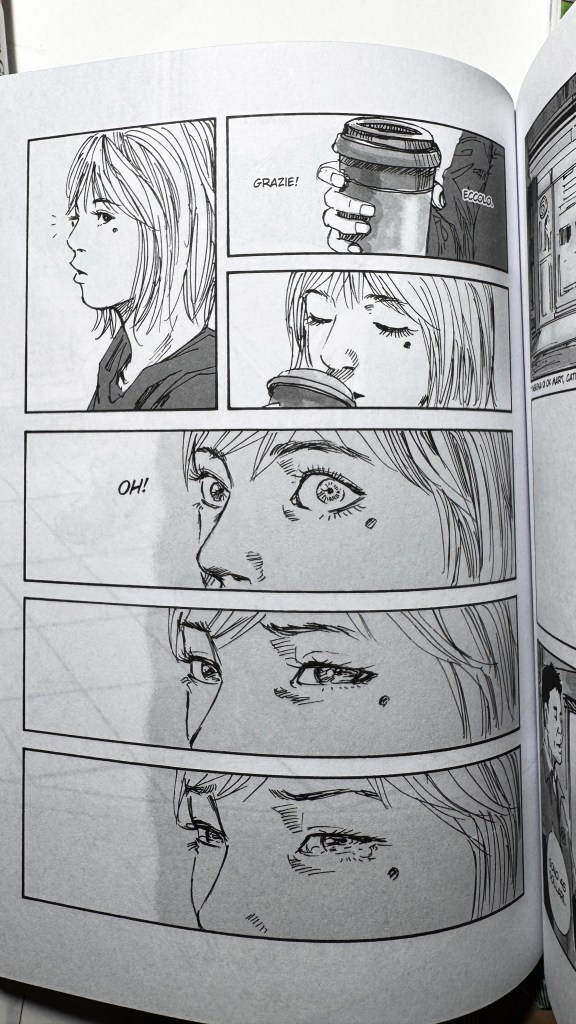

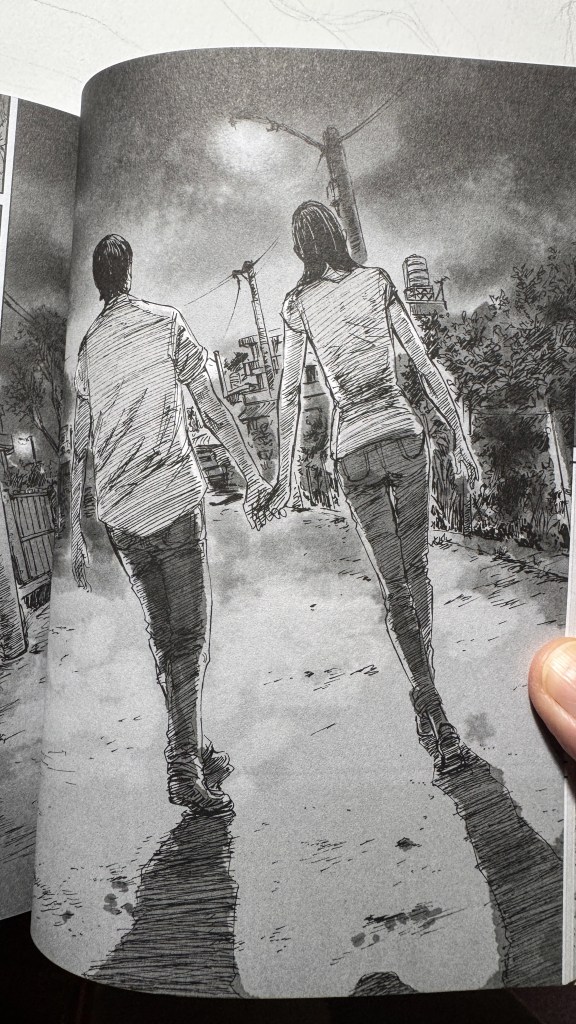

La cosa che balza immediatamente all’occhio è lo stile grafico: un tratto nervoso da real g-pen (Tsukumitsu lavora con Clip Studio Paint), affilato, tremolante e con una grande contrapposizione tra l’essenzialità quasi astratta dei volti delle ragazze, ottenuti da segni praticamente circolari, e l’affastellamento di dettagli degli sfondi. La piattezza grafica delle personagge si staglia contro una prospettiva profondissima che non può non ricordare Blame! e perfino il manga di Nausicaä.

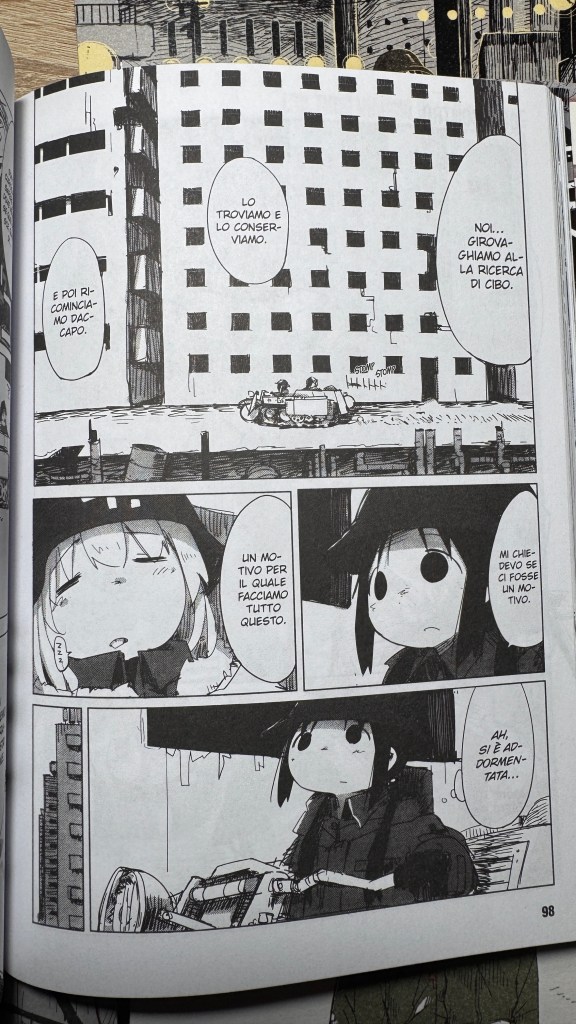

Subito capiamo che gli elementi “apocalisse+ gita fuori porta” sono contemporaneamente presenti grazie allo stile narrativo portato come uno slice of life, ma l’ambientazione è postapocalittica.

I contrasti non finiscono qui, perché Chito e Yuri sono antitetiche a loro volta, e nel loro comportamento, specie in Chito, c’è una certa crudeltà, violenza, mentre Yuri è più razionale e curiosa. Yuri e Chito sono sorelle (credo, o forse cugine). Potrebbe esserci un altro tipo di legame, io però non l’ho percepito, tuttavia alcune volte in italia il titolo è stato considerato inseribile tra gli “yuri-seinen”.

Analizzando attentamente si capisce quanto Tsukumitsu abbia letto di Arte, del manga classico e moderno e quanto impatto abbia avuto su di lui Akira Toriyama (a sua volta non esente dalle influenze dell’illustrazione occidentale di metà Novecento, come Norman Rockwell). Si potrebbe a volte pensare che lo stile di disegno sia frettoloso, in realtà è solo nervoso, ma mai impreciso, e anzi, è dettagliatissimo senza essere dovizioso o affastellato. Rivela anche una grande conoscenza della prospettiva e dell’anatomia: Tsukumitsu è la classica persona che pensa una cosa e la disegna come l’ha pensata, senza nessun riferimento. Non c’è riferimento possibile per quelle scenografie, se non nella propria fantasia. L’interpolazione grafica è attraverso il filtro della grande Arte Informale, di Joan Miró, Paul Klee, Picasso, Brancusi, il Razionalismo architettonico, Le Corbusier.

La gabbia sempre lineare e molto regolare rende il racconto ben scandito e semplice da seguire, ma anche distaccato, in modo che *l* lettor* non sia trasportato troppo dentro alla distruzione del mondo e si aggrappi invece al tepore dell’ingenuità delle due protagoniste. L’azione è scandita senza prospettive esagerate, appiattita quasi di forza per non essere mai “troppa” e generare contrasto con lo scenario. Questo è genio, eh. Il mondo distrutto viene narrato e attraversato come in una fiaba. Che volpone, Tsukumitsu!

Insomma, leggetelo, perché è veramente poetico.

“Girls’ Last Tour” by Tsukumizu, Goen Editions, a little-known gem

Scroll down for the English and Japanese versions (translated with ChatGPT)

I have been saying for years that original manga and book titles should be written with kanji, not just in rōmaji. Girls’ Last Tour plays on the ambiguity of the pronunciation shūmatsu, which to the ear can mean either “weekend” or “end of the world”. The title in kanji is 少女終末旅行, literally “the girls’ journey to the apocalypse” (shūmatsuron being eschatology), but it could also read as “a weekend outing trip”. And this double meaning is Tsukumizu’s sly trick: Japanese readers enter the manga with dual expectations – is it dystopian or slice‑of‑life? We couldn’t pull off the homophone in Italian, but Tsukumizu, a real fox, uses it masterfully. I won’t say more, this little masterpiece must stay spoiler‑free.

What immediately strikes the eye is the art style: a nervous line from a real g‑pen (Tsukumizu works with Clip Studio Paint), sharp, trembling, with a stark contrast between the almost abstract simplicity of the girls’ faces – formed by near‑circular strokes – and the pileup of background details. The flat graphical representation of the characters strikes a a profound perspective that inevitably evokes Blame! and even Nausicaä.

Then it becomes clear that the “apocalypse + weekend outing” elements exist simultaneously through a slice‑of‑life narrative style, despite the post‑apocalyptic setting.

The contrasts don’t end there. Chito and Yuri are antithetical: Chito sometimes shows cruelty and violence, while Yuri is more rational and curious. They seem like sisters (or maybe cousins). Some Italian fans have even classified the title as “yuri‑seinen,” though I didn’t perceive that myself.

A close reading reveals how deeply Tsukumizu has studied art and classic manga, and how much influence Akira Toriyama has had on them — in turn influenced by mid‑20th‑century Western illustrators like Norman Rockwell. The drawing style may sometimes appear hurried, but it is actually nervous and never sloppy. It is extremely detailed without being ornamental or cluttered. The work reveals a strong understanding of perspective and anatomy: Tsukumizu is the kind of creator who imagines something and draws it precisely as they’ve pictured it, with no external reference. Those scenographies are purely from imagination. The graphic interpolation is filtered through Informal Art giants like Joan Miró, Paul Klee, Picasso, Brâncuși, and architectural Rationalism — Le Corbusier.

The panels are always linear and very regular, making the story rhythmic and easy to follow but also detached—so the reader doesn’t get swept into the world’s destruction and instead holds onto the warmth of the girls’ innocence. The action is deliberately flattened—never “too much”—to contrast with the setting. This is genius. The destroyed world is narrated and traversed like in a fairy tale. What a fox, Tsukumizu!

つくみず著『少女終末旅行』(Goen出版)、知る人ぞ知る小さな宝石

英語版と日本語版(ChatGPTによる翻訳)をスクロールしてご覧ください。

私はずっと、マンガや書籍の原題は漢字で書くべきで、ローマ字だけでは不十分だと主張してきました。『少女終末旅行』は「終末(しゅうまつ)」という発音の曖昧さを巧みに利用しています。「しゅうまつ」は耳では「週末=週末」か「終末=世界の終わり」のどちらにも聞こえます。タイトルの漢字は 少女終末旅行、文字通り「少女たちの終末への旅」(終末論=エシュカトロジー)ですが、「週末の遠足」としても読めます。この二重の意味こそがつくみずの狡猾さで、日本人読者は「これはディストピア? それともスライス・オブ・ライフ?」という二重期待を抱いて作品に入るのです。イタリア語では同音異義が再現できませんでしたが、つくみずは見事にそれを使いこなしています。これ以上は言いません。この小さな傑作はネタバレ厳禁です。

まず目を引くのはそのグラフィックスタイルです。実際のgペンのような緊張感ある線(つくみずはClip Studio Paint使用)、鋭く震えるようなタッチ、少女たちの顔はほぼ円形の記号で描かれた抽象的な構成、一方で背景には膨大なディテールがびっしり詰め込まれています。キャラクターの平面的表現と深遠な遠近法の背景との対比は、必然的に『BLAME!』や『風の谷のナウシカ』を想起させます。

次に気づかされるのは、「終末+週末の遠足」という要素が、スライス・オブ・ライフ的な語り口で同時に成立していることです。舞台は明らかにポスト・アポカリプスですが、淡々とした日常の延長として語られます。

対比はさらに深く、チトとユーリは相反する性格を持っています。チトには時に残酷さや暴力性が見え、ユーリはより理性的で好奇心旺盛。姉妹(あるいは従姉妹?)のような関係性ですが、イタリアでは“百合セイネン”として分類される場合もあります(私はそこまで感じませんでしたが)。

つくみずがいかに美術や古典マンガを読み込んでいるか、また鳥山明からどれほど影響を受け、その鳥山明がさらにノーマン・ロックウェルなど20世紀中頃の欧米イラストに影響されたかが見えてきます。描線は時にせっかちに見えて実は緊張感があり、決して不正確ではありません。装飾的でも雑でもない非常に緻密な描写で、遠近法や解剖学の知識も豊富です。つくみずは想像したものをそのまま紙に描くタイプの作家で、背景にモデルはありません。あの舞台装置はすべて彼らの想像力から生まれています。グラフィック表現にはミロ、クレー、ピカソ、ブランクーシといったアンフォルマルアートの巨匠、および建築ラショナリズム、ル・コルビュジエらの影響が感じられます。

コマ割りは常に直線的で整った構成なので、物語にリズムがあり読みやすく、それでいて距離感があります。読者が世界の破壊に“飲み込まれる”ことなく、少女たちの純粋な暖かさにしがみつけるように設計されています。アクションは意図的にフラットで“過剰”にならず、背景とのコントラストを生んでいます。これが天才的なんです。壊れた世界は、まるでおとぎ話のように語られ、歩む。つくみず、なんてずる賢いんだ!

向下滚动阅读中文版本。由 ChatGPT 翻译。Scroll for the English version (translated with ChatGPT)

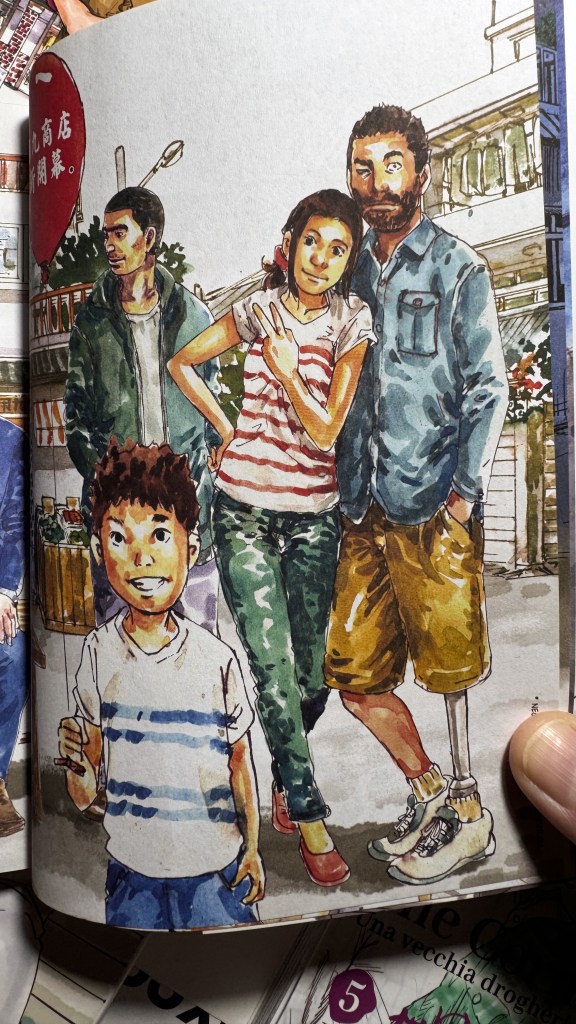

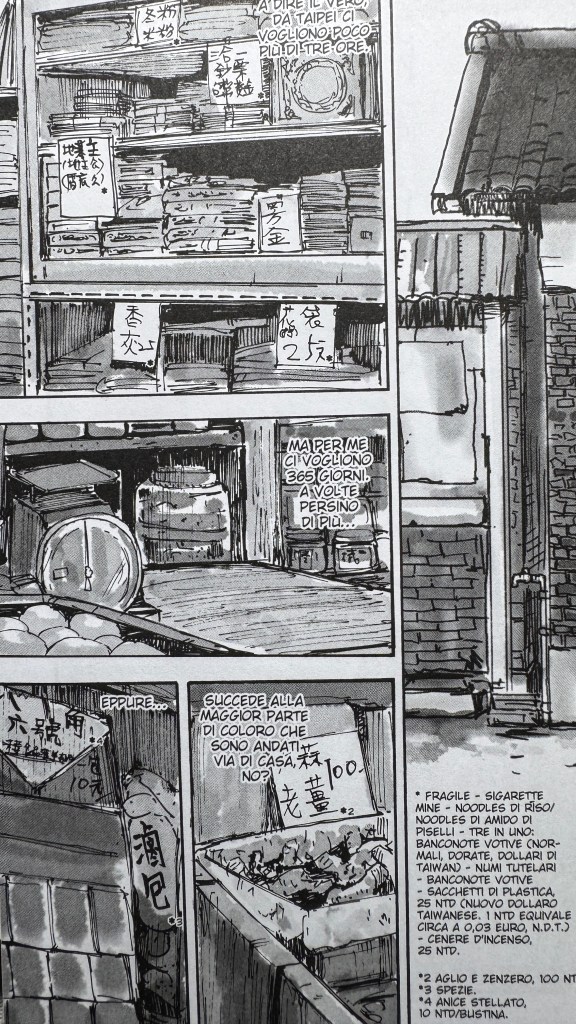

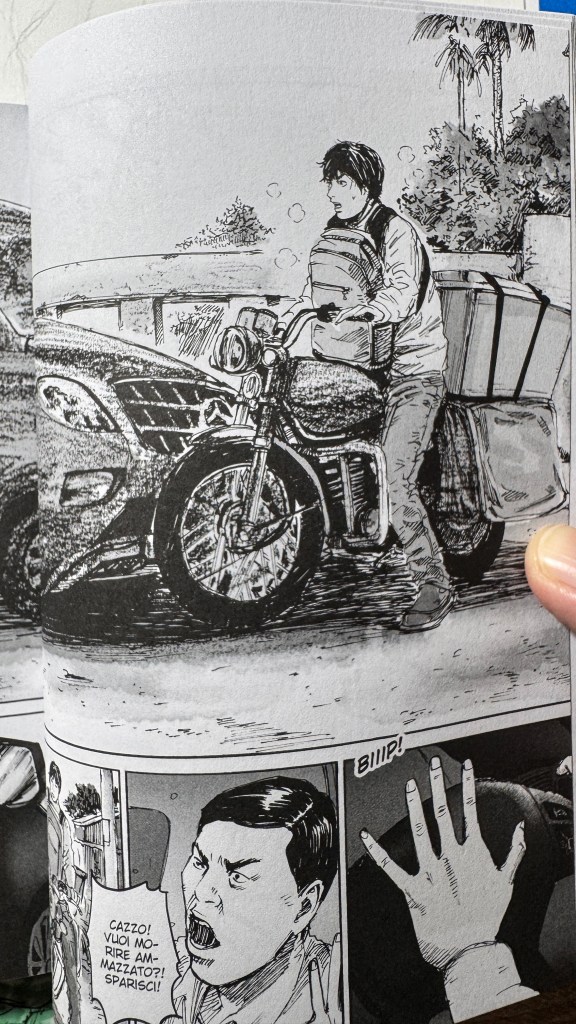

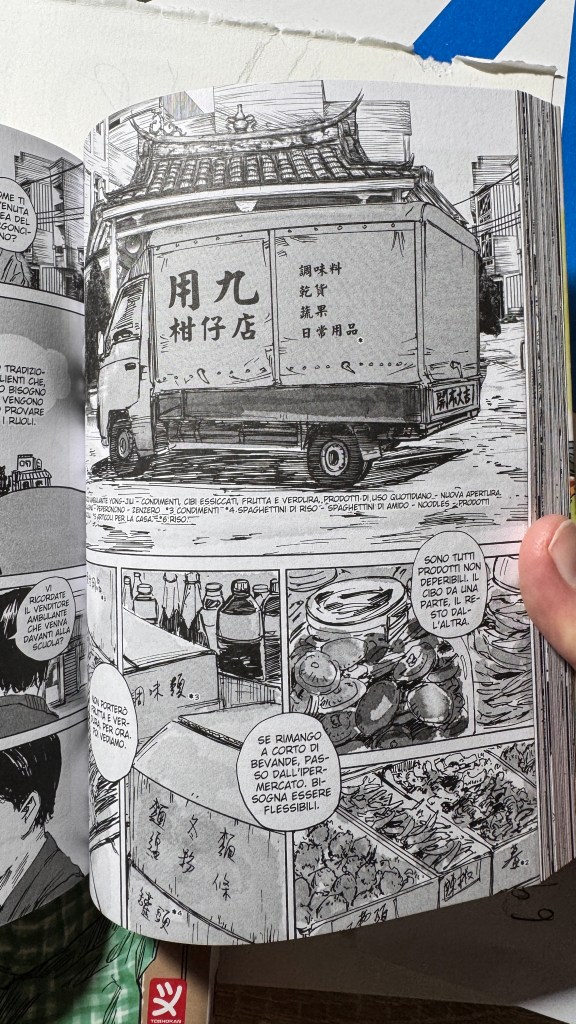

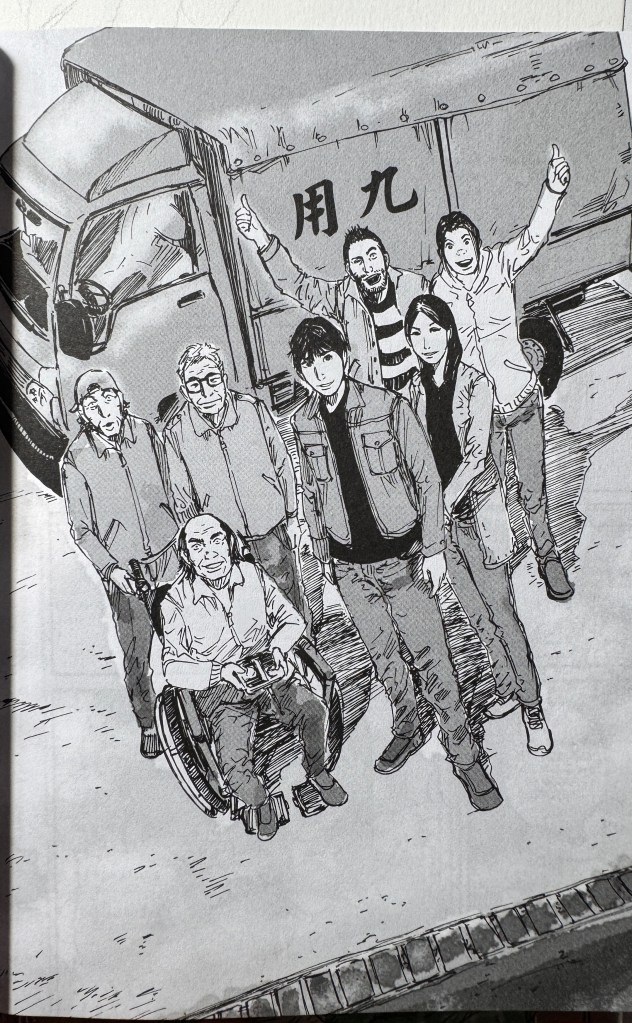

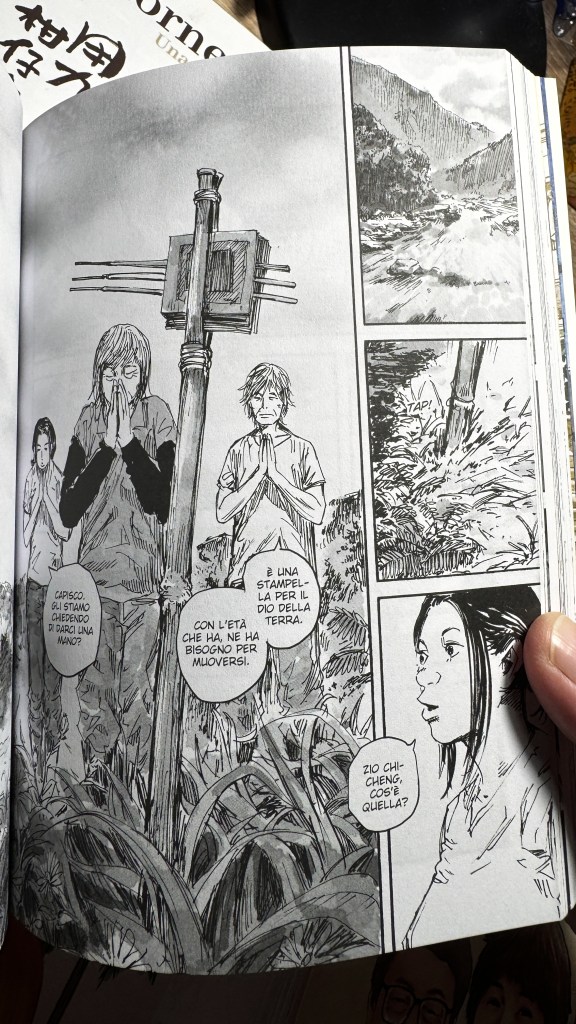

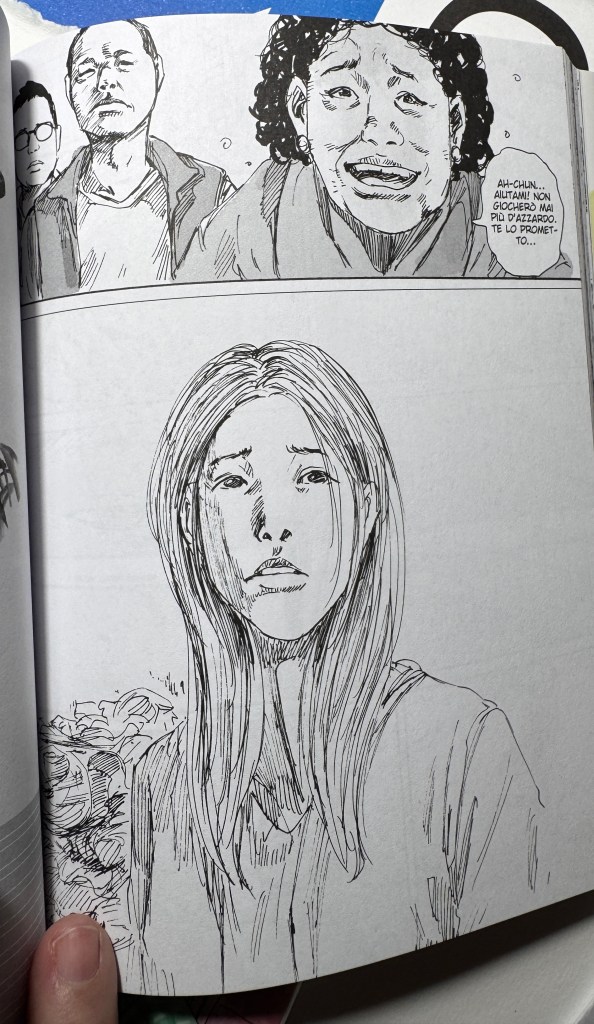

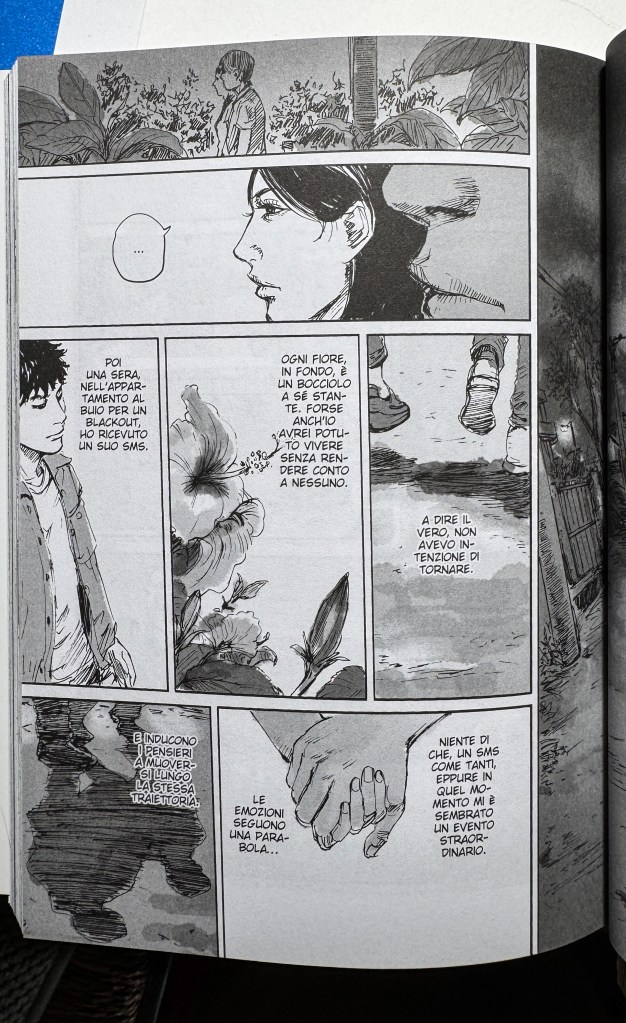

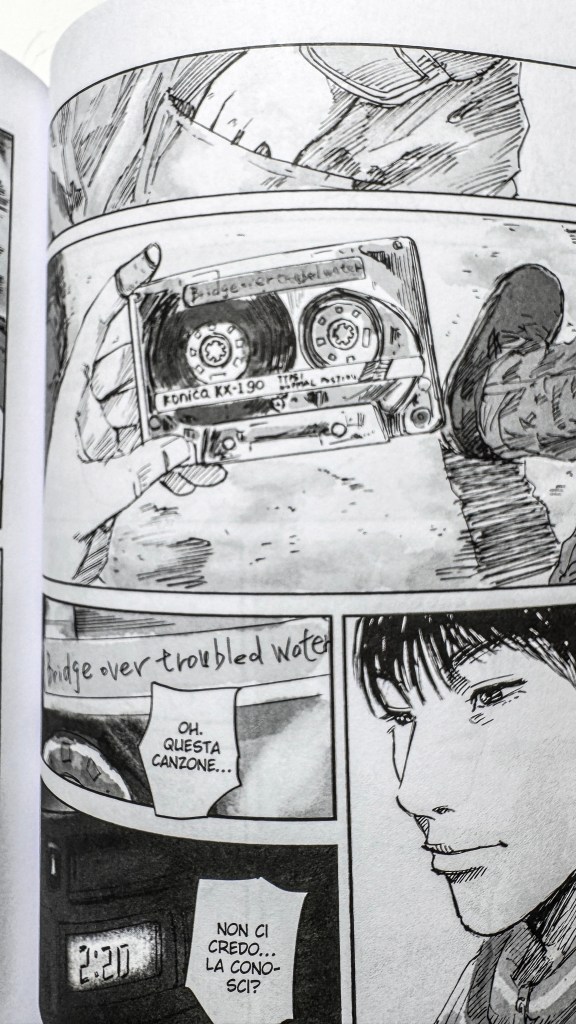

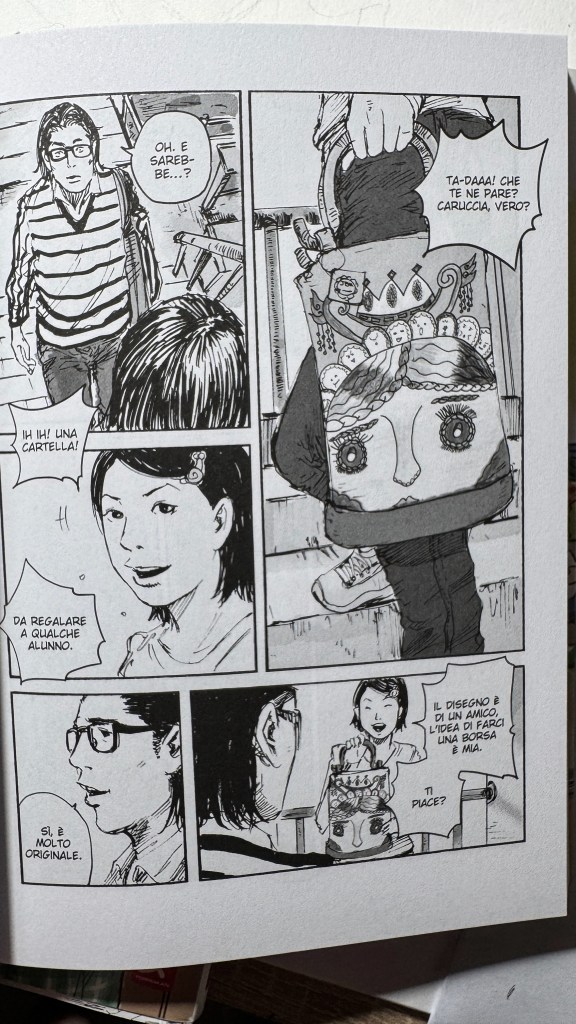

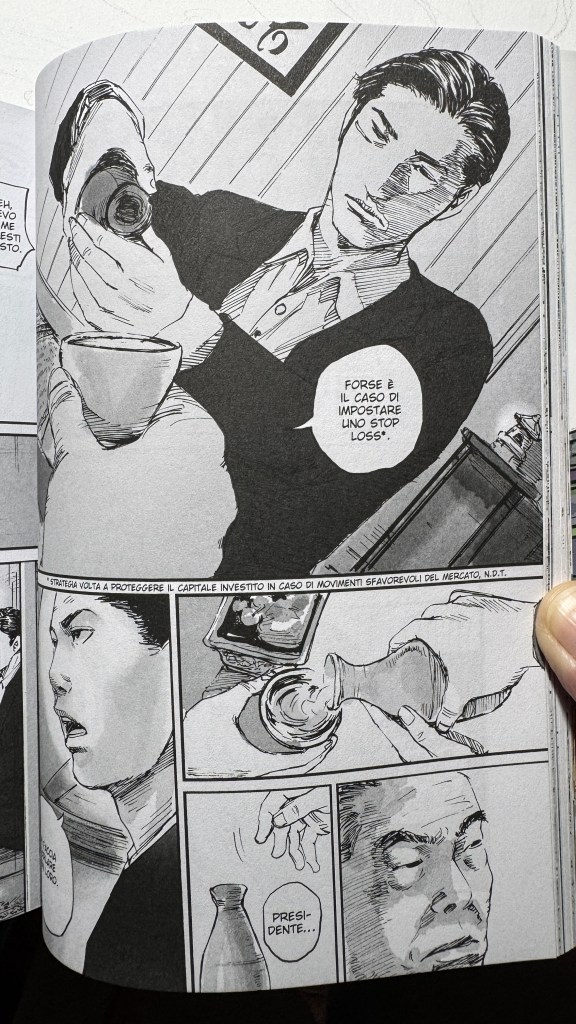

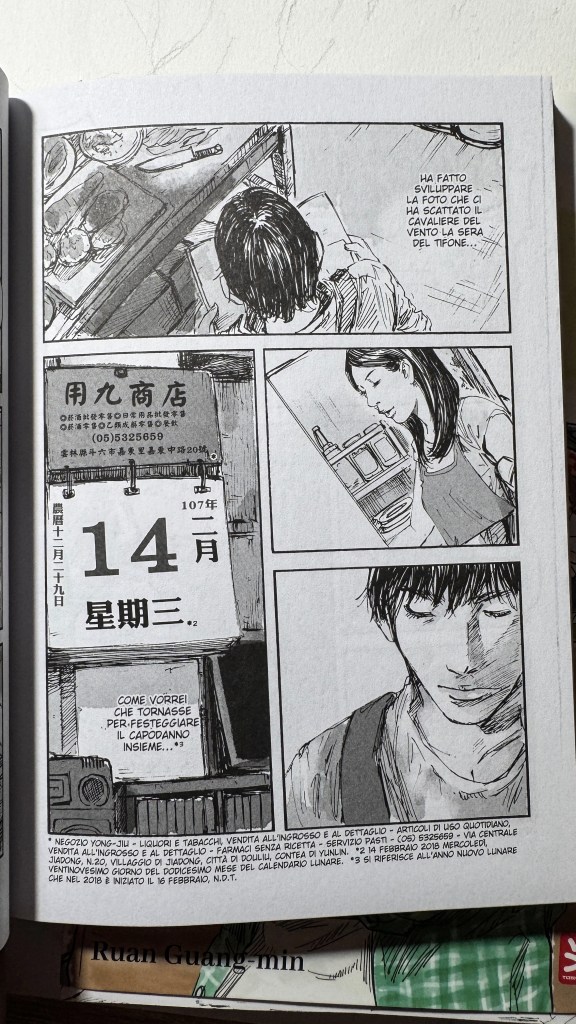

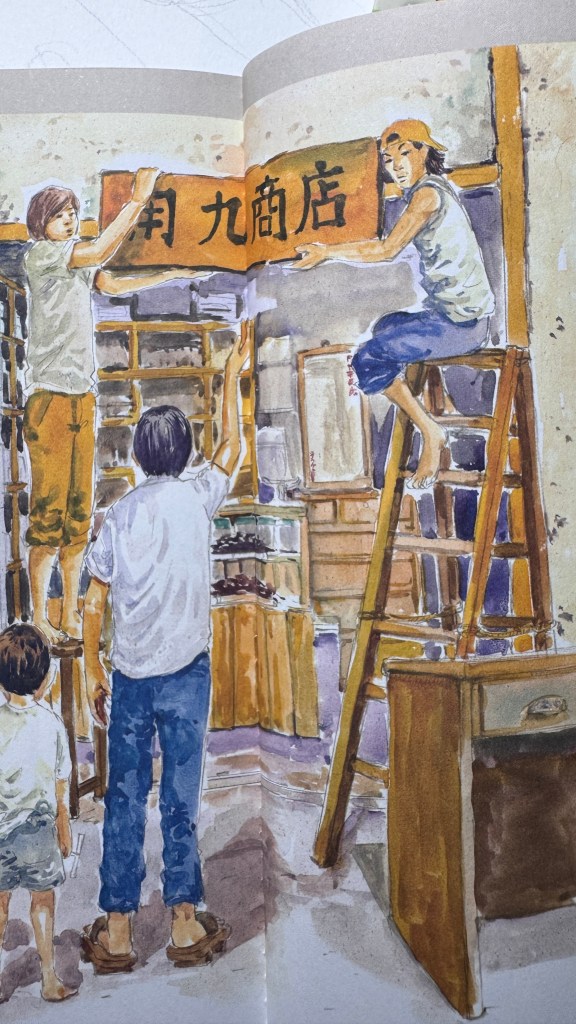

The corner store. Una vecchia drogheria è una delle uscite migliori degli ultimi anni. Sorprendente è dire poco. Ruan Guang-min, un autore taiwanese, porta in scena un insieme di personaggi normali, comunissimi, e certamente più interessanti dei vari superpotenziati che abitano i manga giapponesi. Il manhua taiwanese è largamente inesplorato in Italia, anche in alcune delle sue vette artistiche (come Chen Uen o Little Thunder). Da pochi anni la casa editrice Toshokan ne sta traducendo alcuni, con grandissimo favore del pubblico più maturo e raffinato.Guang-min è molto noto in patria per avere centrato storie corali imperniate su piccole attività commerciali di famiglia, ha vinto numerosi premi e i suoi manhua vengono trasposti in serie televisive. The corner store sente certamente l’andamento del drama, dello sceneggiato, non solo nel succedersi degli eventi, ma anche della scansione dell’azione in pagina, della prospettiva, dell’inquadratura. Guang-min è senza alcun dubbio uno dei migliori artisti che circolano tra gli scaffali italiani, la sua tecnica di disegno è sorprendente per l’efficacia, per l’icasticità, la velocità con cui la rappresentazione raffigurata diventa vivida, reale, vicina. La sua capacità di far correre l’occhio e la lettura è straordinaria. In questo lo ritengo supremo, inarrivabile.

Lui disegna in digitale ma il tratto rimane sempre molto artigianale, con delle sporcature tipiche del carboncino, della matita grassa passata di taglio sul cartoncino ruvido. Non si perdono le linee ravvicinate dello schizzo a matita e a pennino, le finezze del pennello. Una attenzione allo strumento utilizzato che è praticamente ignota a molti mangaka giapponesi, che ci danno sempre un tratto fine e pulito, perfetto e anonimo, e che in Europa viene invece molto apprezzata poiché segno caratteristico e distintivo di una sola mano, di un unico individuo. L’unicità, la riconoscibilità, è sempre un elemento positivo per l’occhio europeo, poiché avvicina l’artista alla creazione divina.

L’emozione che mi ha suscitato questo manga è di una immensa nostalgia di qualcosa che non ho mai posseduto. Sono una X Gen, i “corner store” esistevano ai miei tempi, anzi, non c’era altro tipo di negozio. Si chiamavano “bottega”, “emporio”, “spaccio”, o meglio ancora, con il nome del proprietario. “Vado dal Carlino, dal Ieraci, da Torre”, oppure si usava il soprannome paesano “il Magnamagna”, “il Brigante”.

Per me erano posti terribili, dove andare perché necessario, per una richiesta ricevuta in famiglia, che per una bambina diventa un ordine. Lì dentro mi sentivo un agnello il mezzo ai lupi, un pezzo di carne da pesare, una merce da poter acquistare semplicemente prendendola dallo scaffale. Sin da piccola sentivo il puzzolente fiato del patriarcato sul mio collo. Gli sguardi sezionatori dei “vecchi” (magari quarantenni) che indugiavano sul mio corpo di scolara elementare come se fossi una sugosa pietanza ambulante. Le donne adulte o erano acquirenti, quindi di passaggio, oppure mogli dei titolari, quindi ipostasi dei mariti. Le bambine non sarebbero state ammesse in bottega, nemmeno se figlie del titolare. Troppi maschi, troppi vizi, alcool, sigarette, possibilità di violenza, e non ultima, la vicinanza al mondo del danaro, dell’attività commerciale, da cui le femmine venivano accuratamente tenute lontane.

Perciò il pensiero che avrei potuto aspettare il bus alla bottega, o fare i compiti assieme agli altri bambini, mangiucchiando biscotti, come hanno fatto i protagonisti di The corner store, mi ha letteralmente assestato una coltellata nelle costole. A me, questa vita, questi ricordi, che probabilmente sono condivisi da molti miei coetanei maschi, sono stati negati poiché nata femmina. E mi chiedo quanta distanza ci sia tra i negozietti d’angolo della remota provincia calabrese degli anni ’70-’80 e quelli della provincia taiwanese di qualche anno fa. Mi chiedo se le millennial di Taiwan abbiano sentito anche loro il peso dello sguardo maschile andando a prendere un ghiacciolo. E inevitabilmente mi dico di sì.

E questa cosa mi fa arrabbiare, e mi addolora.

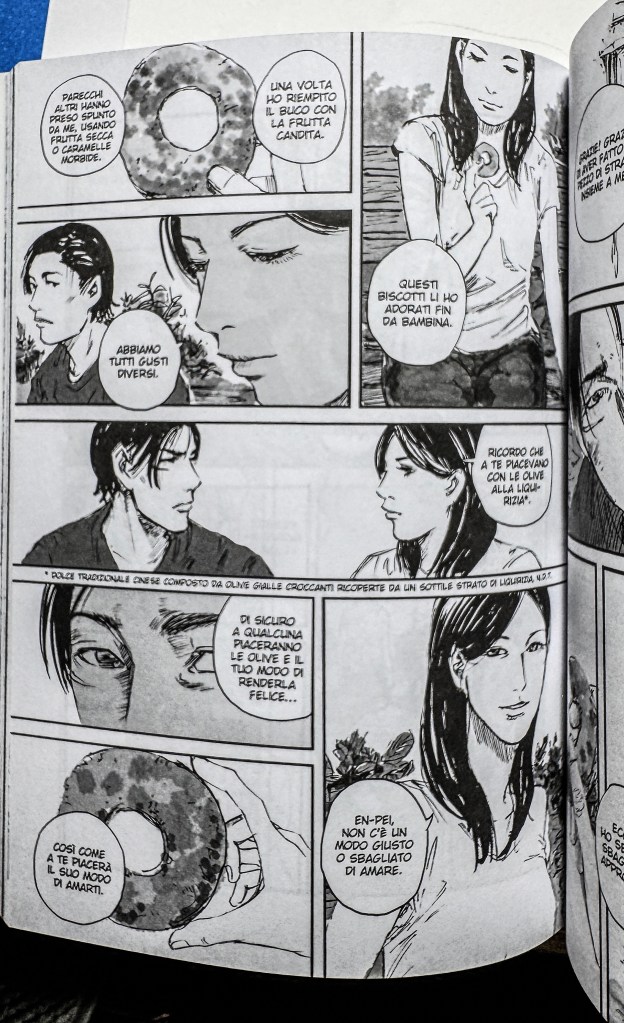

Nel racconto di Guang-min i personaggi femminili non mancano, ma quelli importanti sono solo tre rispetto agli innumerevoli maschi. Tutte e tre sono legate a temi romantici, e una soltanto ha una caratterizzazione forte al di fuori della sfera sentimentale. Se tra i maschi avvengono dialoghi e considerazioni sul senso della vita, sui propri sentimenti e sul commercio, questo non avviene tra i personaggi femminili, che si sovrappongono o si lambiscono occasionalmente, spesso senza avere una reale interazione che non sia la condivisione dello spazio nella pagina. Manca anche un analogo rapporto intergenerazionale che si sviluppa attorno al protagonista maschile.

La lettura è sempre molto piacevole, davvero commovente. Ma si avverte questo ronzio, il rumore di fondo, quella distorsione della realtà data dall’ assenza di metà del mondo. Se il manga giapponese è tristemente famoso per questa assenza o per la trasfigurazione delle donne in bambole scervellate, in una narrazione di persone ordinarie era legittimo avere una aspettativa più alta. Qui la scarsa presenza femminile non è una scelta editoriale, ma viene spontanea come specchio della società.

Se mi soffermo su questo punto invece che sulle altre qualità del fumetto è per due ragioni: la prima è che questa serie ha ricevuto moltissimi consensi e recensioni, e gli aspetti tecnici e narrativi sono stati già ampiamente esplorati. La seconda è è perché ritengo sia molto importante sottolineare come spesso i maschi descrivano un mondo a metà (le recensioni scritte da donne sono ancora troppo poche, sempre indulgenti o poco attente alla rappresentazione mediatica dei generi). Noi donne siamo abituatissime a immedesimarci in personaggi maschili, ecco perché il female gaze ci sconvolge sempre, o la ragione dell’enorme successo dei boy’s love.

Sentirsi tagliate fuori da un racconto di supereroi è brutto, ma se succede in una storia di persone ordinarie, si sente un dolore tanto forte quanto più è bella l’opera. E The corner store è veramente bellissimo. La vitalità dell’andamento narrativo, mescolata a temi umani così forti e toccanti, l’espressività dei personaggi, rendono questo manhua un vero tesoro, quel tipo di racconto da leggere e rileggere nell’arco del tempo, nel quale rivedersi, ogni volta cambiati (e uso il maschile di proposito) a seconda dell’età, delle scelte di vita. A colpire direttamente è però l’abilità artistica di Guang-min, che ha uno stile molto incisivo, carico nel segno ma privo di orpelli, che insiste nel dettaglio pur concedendosi la sporchevolezza della bozza. Una magia che pochi artisti sanno fare.

Personalmente ho apprezzato molto il personaggio di En Pei, proprio per la sua scelta (e anche perché è molto carino).

Da rimarcare lo splendido lavoro fatto dall’editore Toshokan sulla traduzione e sulle note, che hanno spesso occupato una parte considerevole dei margini.

Ruan Guang-min è anche un artista molto social e estremamente disponibile e alla mano: risponde sempre a tutti e tutte con parole di ringraziamento e gentilezza. Questo è il suo account Instagram, dove pubblica spesso anche disegni a colori da lasciare senza fiato.

漫画正是以这句话结束的:如果能够接受对方的缺点,那就是真爱。也许对漫画来说也适用吧?我想是的。

《小角落杂货店》(The Corner Store)是近年来最出色的新作之一,用“令人惊艳”来形容都显得太轻了。台湾漫画家阮光民带来了一群平凡普通的人物,比起那些充斥日本漫画的超能力角色,他们真实得多,也有趣得多。

台湾的漫画(manhua)在意大利基本上还是一片未被开发的领域,即使是像陈又宁、Little Thunder这样达到艺术高峰的作品也鲜有人知。最近几年,Toshokan出版社开始翻译一些台湾漫画,深受成熟且品味独特的读者群体欢迎。

阮光民在台湾非常有名,擅长描绘以家庭小型商店为背景的群像故事,赢得了无数奖项,他的作品也常常被改编成电视剧。《小角落杂货店》充满了电视剧般的节奏感,不仅体现在故事的发展上,也体现在分镜、透视、构图等画面布局上。

阮光民无疑是目前意大利书店里最杰出的艺术家之一。他的绘画技巧令人惊叹:画面生动、凝练、充满现实感,几乎一瞬间就能把读者带入故事之中。他让眼睛和思绪飞驰流动的能力,堪称无敌。对此,我认为他是至高无上的,无可匹敌。

虽然他使用数位工具作画,但笔触依然非常有手工感,保留了炭笔、粗糙铅笔在粗纸板上划过的那种质感。

他从不抹去铅笔或钢笔速写的紧密线条,细致的笔刷处理也清晰可见。对绘图工具细腻的掌控,在许多日本漫画家那里是很少见到的——他们往往追求细腻干净、完美而略显无个性的线条。而在欧洲,这种独特、辨识度高的个人风格反而非常受到推崇,因为它让艺术家显得像是独自创世的存在。

独特性与辨识性,始终是欧洲读者眼中极其正面的价值。

这部漫画给我带来了一种对未曾拥有过的东西的巨大怀念。我是X世代,当年,”corner store”(街角杂货店)确实存在,事实上,那个时候只有这种店铺。它们被叫作“杂货店”“百货店”“供销社”,或者直接叫店主的名字,比如“去卡尔利诺家”、“去耶拉奇家”、“去托雷家”,又或者用乡村的绰号,“去大胃王家”、“去土匪家”。

对我来说,那些地方是令人害怕的地方,必须去,是因为家里交代了任务,对一个小女孩来说,就是无法抗拒的命令。

走进去,我仿佛是一只走入狼群的小羊,是一块等待被称重的肉,是货架上可以随手取走的商品。从小我就感受到了那股刺鼻的父权气息。

那些“老男人”(其实可能才四十岁左右)的目光,在我小小的女学生身体上流连,就像在打量一盘新鲜美味的菜肴。

成年女性不是匆匆而过的顾客,就是老板的妻子,是男人的附属品。小女孩则根本不应该出现在杂货店里——那里有太多男人、太多恶习(酒、烟、暴力),还有最重要的,钱与商业的世界,是女孩子被刻意远离的禁地。

因此,当我读到《小角落杂货店》里那些小孩可以在店里做作业、吃饼干、等公交时,我的心仿佛被狠狠地捅了一刀。

这种生活,这样的回忆,可能是很多男性同龄人共有的,而对我而言,仅仅因为是女孩,就被无情地剥夺了。

我不禁想,1970-80年代遥远的卡拉布里亚乡村小杂货店,与近年台湾乡镇的小角落杂货店之间,究竟有多少相似?

台湾的千禧一代女孩,在买冰棒时,是否也曾感受到男性目光的沉重?我想,答案是肯定的。

而这让我愤怒,也让我悲伤。

在阮光民的故事里,虽然也有女性角色,但重要的只有三个,相较之下男性角色却数不胜数。这三位女性角色都与浪漫情节有关,只有一位在爱情之外有着强烈的个性刻画。

男性角色之间有关于人生、情感、商业的对话和思考,而女性角色之间几乎没有真正的互动,顶多是偶尔擦肩而过,在画面上共享同一空间而已。

缺乏女性之间类似的代际传承与联系——而这种联系,男性角色间却是故事主轴之一。

阅读体验依然非常愉快,很多地方令人感动,但背景中,总有一种嗡嗡作响的不协调感:女性的缺席,扭曲了现实的完整性。

如果说日本漫画因女性角色的缺失或异化(变成无脑的娃娃)而臭名昭著,那么在描写普通人生活的作品中,我们本应期待更高标准。

《小角落杂货店》中女性的少数,不是编辑选择,而是自然而然地反映了现实社会。

我之所以特别强调这一点,有两个原因: 第一,这部作品已经收获了大量赞誉和评论,技术和叙事上的优点大家都讲得很多了; 第二,我认为指出这种现象非常重要:男性创作者经常只描绘出一半的世界,而女性评论者又太少,且往往太宽容,或者缺乏对性别呈现的敏感观察。

我们女性早就习惯于代入男性角色了,所以每当遇到真正的“女性视角”(female gaze)时,总会被深深震撼;也因此,boy’s love作品在女性群体中才会如此成功。

如果在超级英雄的故事里被排除在外已经让人心寒,那么在讲述普通人日常生活的故事里被排除,更是深深刺痛人心——尤其是当这部作品本身如此美丽动人时。

《小角落杂货店》正是这样一部杰作。

那种温暖的人情流动,与深刻动人的人生主题交织在一起,加上角色鲜活的表情和动作,成就了这部值得反复阅读、随年龄与人生经历不同而不断有新感悟的珍宝(我这里故意用了男性词形)。

最直接打动人心的,还是阮光民那种独特的艺术技巧——线条厚重有力,但绝不华而不实;细节充沛,却又大胆地保留粗糙与不完美。他掌握的那种“草图中的魔力”,是极少数艺术家才能做到的。

我个人非常喜欢**恩沛(En Pei)**这个角色,特别是因为他的选择(还有,他真的很可爱)。

还要特别表扬Toshokan出版社在翻译和注释上的用心——许多时候,注释占据了大量页面边缘,非常丰富而且清晰。

最后要说,阮光民本人也是一个非常亲切随和的艺术家,超级活跃在社交媒体上。他总是认真、友善地回复所有留言。这是他的Instagram账号,他经常分享一些让人屏息的彩色插画作品

阮光民也是一个非常亲切、极具亲和力的艺术家:

他总是温柔地回复所有粉丝的留言,表达感谢。

这是他的Instagram账号,他时常发布令人屏息的彩色插画。

The comic ends precisely with this sentence: if you accept the flaws, then it’s true love. Maybe it’s the same for manga? I’d say yes.

The Corner Store — an old-fashioned grocery shop — is one of the best releases in recent years. Calling it “surprising” would be an understatement. Ruan Guang-min, a Taiwanese author, brings to life a group of ordinary, everyday characters who are far more interesting than the super-powered ones populating Japanese manga. Taiwanese manhua are still largely unexplored in Italy, even in their artistic peaks (such as Chen Uen or Little Thunder). Only recently has the publisher Toshokan started translating some of them, to great acclaim among more mature and refined readers.

Guang-min is very famous in his home country for his ensemble stories focused on small family-run businesses. He has won numerous awards, and his manhua have been adapted into TV series.

The Corner Store definitely carries the pacing of a drama, not only in how events unfold but also in the way action is laid out on the page — the perspective, the framing. Guang-min is without a doubt one of the best artists currently available in Italian bookstores. His drawing technique is astonishing for its effectiveness, its vividness, and the speed with which the images come to life, feeling real and close. His ability to guide the reader’s eye and reading flow is extraordinary. In this, I consider him supreme, unreachable.

He draws digitally, but his linework always retains a handmade quality, with the smudges typical of charcoal or a soft pencil rubbed sideways on rough paper.

You can still see the close lines of pencil and pen sketches, the finesse of the brush.

Such attention to the tool used is practically unknown to many Japanese mangaka, who often offer clean, thin, flawless (and anonymous) lines — whereas in Europe, this more personal, handcrafted touch is highly appreciated because it reveals the artist’s individual hand.

Uniqueness, recognizability, is always a positive element for European eyes, as it brings the artist closer to the divine act of creation.

The emotion this manhua stirred in me was an immense nostalgia for something I never actually had.

I’m from Generation X — “corner stores” existed in my time; in fact, there weren’t any other kinds of shops. They were called “bottega”, “emporio”, “spaccio” — or, better yet, by the owner’s name: “I’m going to Carlino’s, Ieraci’s, Torre’s.”

Or sometimes by their nickname: “Magnamagna” (Big Eater), “the Brigand”.

To me, they were terrible places — places you went because you had to, often for a family errand which, for a little girl, felt like an unbreakable command. Inside, I felt like a lamb among wolves, a piece of meat to be weighed, merchandise that could be plucked off a shelf.

Even as a child, I could feel the foul breath of patriarchy on my neck.

The scrutinizing stares of the “old men” (often barely forty) lingering on my elementary-school girl’s body as if I were a tasty, walking morsel.

Adult women were either customers — thus fleeting presences — or the shop owners’ wives — mere extensions of their husbands.

Little girls weren’t really welcome in those shops, not even if they were the owners’ daughters.

Too many men, too many bad habits — alcohol, cigarettes, the ever-present risk of violence — and not least, the proximity to the world of money and business, from which females were carefully kept away.

So the idea that I could have waited for the bus at a shop, done homework together with other kids while munching on cookies — as happens to the protagonists in The Corner Store — felt like a stab in the ribs.

This life, these memories, which were probably shared by many of my male peers, were denied to me simply because I was born female.

And I wonder how far removed the little corner stores of rural Calabria in the ’70s and ’80s really are from those in Taiwanese provinces just a few years ago.

I wonder if millennial girls in Taiwan, too, felt the weight of male gazes when buying a popsicle.

And inevitably, I tell myself — yes, they did.

This thought both angers and saddens me.

In Guang-min’s story, there are female characters, but only three important ones compared to the countless male ones.

All three are tied to romantic subplots, and only one has a strong characterization outside of sentimental themes.

While the male characters have conversations about the meaning of life, emotions, and business, this kind of exchange doesn’t happen among the female characters, who merely overlap or brush against each other, often without meaningful interaction beyond sharing space on the page.

There’s also no intergenerational bond among the women like there is around the male protagonist.

The reading experience remains very pleasant and truly moving.

But there’s this constant hum, this background noise — the distortion caused by the absence of half the world.

If Japanese manga are sadly notorious for this absence or for turning women into brainless dolls, in a story about ordinary people, one might have hoped for something better.

Here, the underrepresentation of women isn’t an editorial choice: it feels natural, a mirror of society.

If I’m focusing on this aspect rather than the other many qualities of the comic, it’s for two reasons:

First, because this series has already received plenty of praise and reviews discussing its technical and narrative strengths.

Second, because I believe it’s crucial to highlight how often men describe only half the world (and how there are still too few female reviewers, often overly forgiving or not very attentive to gender representation).

We women are very used to identifying with male characters — that’s why the female gaze shocks us so much, and partly why boy’s love stories are so incredibly popular.

Feeling excluded from a superhero story is painful; feeling excluded from a story about ordinary people is even worse — especially when the work is so beautiful.

And The Corner Store is truly beautiful.

The vitality of the narrative flow, the touching human themes, and the expressiveness of the characters make this manhua a true treasure — the kind of story you reread over time, finding yourself in it again and again (and yes, I’m using the masculine consciously) depending on your age and life choices.

What strikes directly, however, is Guang-min’s artistic skill: his style is bold yet stripped of frills, deeply focused on detail while still embracing the roughness of a sketch.

A magic that few artists can achieve.

Personally, I really appreciated the character of En Pei, both for her choices and because — well — he’s also very handsome.

It’s worth highlighting the excellent work done by publisher Toshokan on the translation and notes, which often took up a significant part of the margins.

Ruan Guang-min is also a very social and extremely approachable artist: he always replies to everyone with words of gratitude and kindness. This is his Instagram account, where he often posts breathtaking illustrations.

groggy

"Quando guardiamo il cielo di notte ci soffermiamo ad ammirare le stelle a caso senza seguire uno schema.. lasciamo che la nostra fantasia si perda in questo immenso soffitto brulicante di luci... una stella grande.. qualcuna piccola.. un'altra azzurra ed una rossa! Luci lontane che forse ora non esistono neanche più.. eppure sono lì le guardiamo ogni sera quando le nuvole ce lo permettono.. luci che continuano a brillare .. a vivere.. che continuano a farci sognare! Questo BLOG vuole essere uno spazio semplice, senza pretese, uno spazio dove antichi sorrisi e sguardi continuano a brillare come stelle... semplicemente continuano a vivere nell'immenso cielo della rete." (Domenico Nardozza)

Rassegne di Scienze Naturali

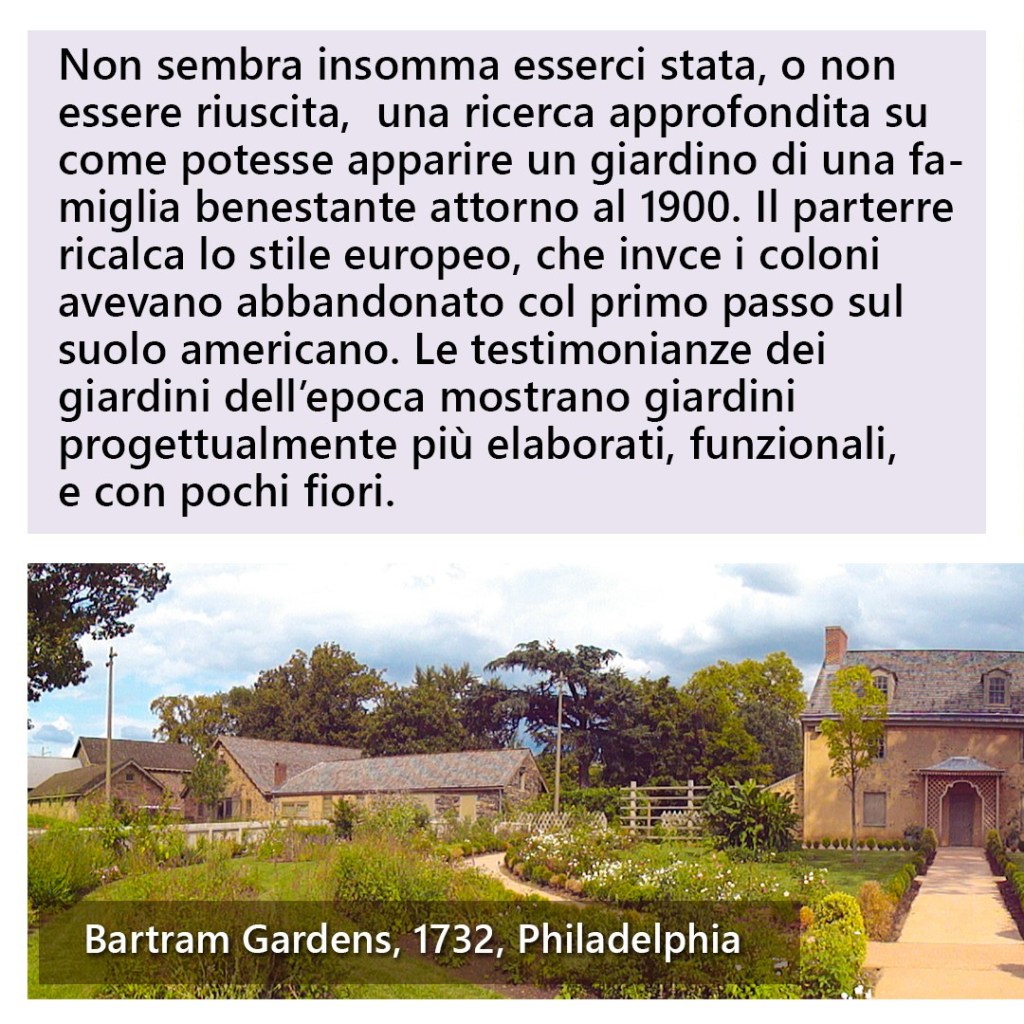

Non mettere a dieta la tua identità